New Study: Winter Bird Numbers Declining in Acadia

The data indicates a 43% reduction in the total number of birds over the 51-year study.

January 5th, 2023

The data indicates a 43% reduction in the total number of birds over the 51-year study.

January 5th, 2023

A blue jay basks in the sunrise on Sargent Mountain. (Photo by Avery Howe/Friends of Acadia)

We can learn a great deal about our changing environment by watching birds.

Shifts in bird populations over time – their presence or absence and growing or waning numbers – is valuable information for researchers. That data prompts inquisition – figuring out what’s causing the population shifts – as well as stewardship to protect threatened species (as was the case for peregine falcons in Acadia National Park).

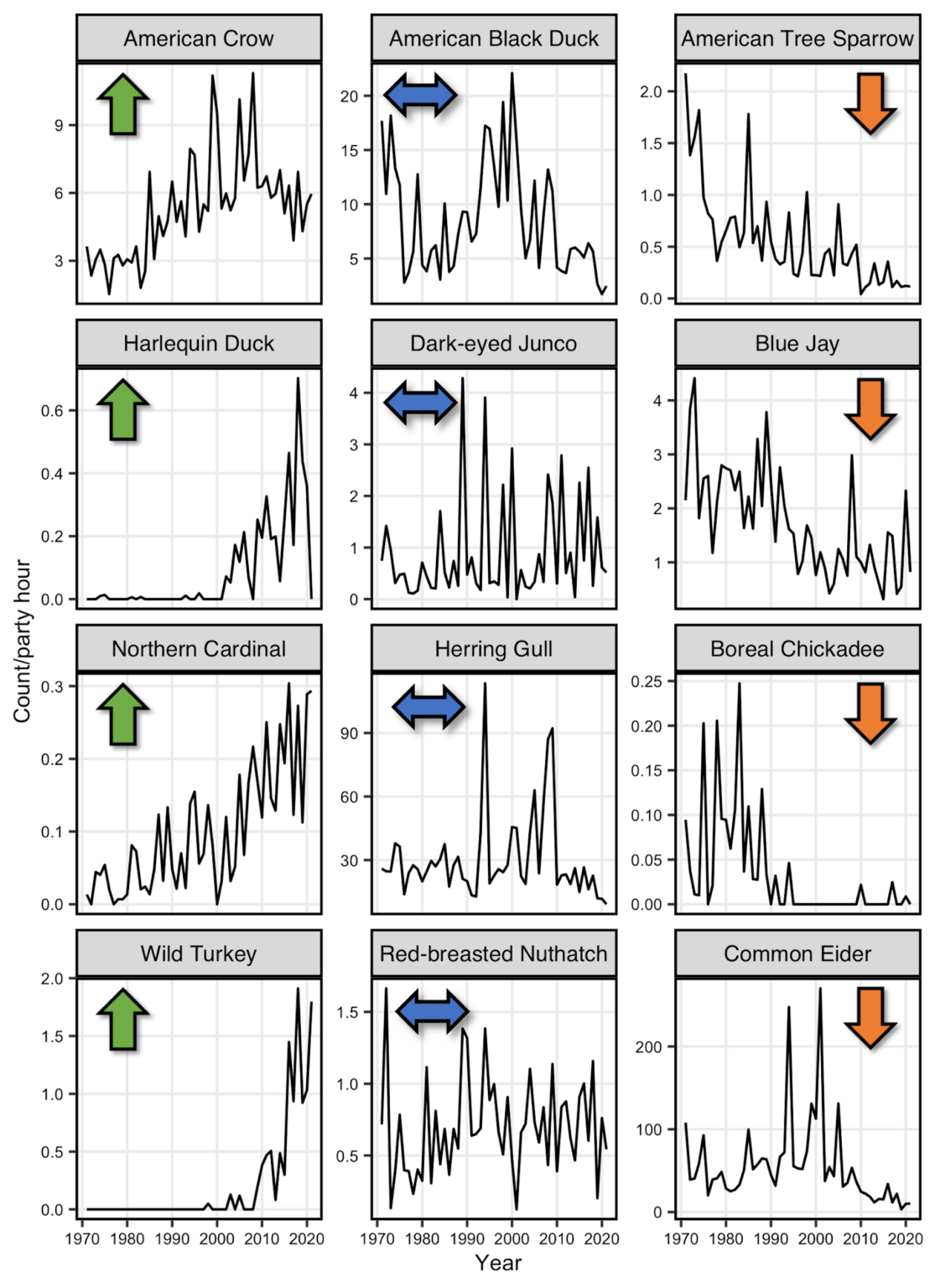

For 51 years, volunteers in and around Acadia National Park have participated in an annual Christmas Bird Count. The data they collect helps assess winter bird population dynamics and species trends. According to a recently published study, the data indicates a “43% reduction in the total number of birds over the 51-year study, with 42 species exhibiting declines, and 33 species showing increasing abundance. The annual number of species observed has declined by over 7%; however, the cumulative species in the full dataset continues to increase as newly observed species are added in most years.”

The full study, published in Northeast Naturalist, is available here: Acadia National Park Winter Birds: 51 Years of Change Along the Coast of Maine

Graphic by Schoodic Institute

The study was led by Schoodic Institute data analyst Kyle Lima. Here’s an excerpt from a story about the research from the Schoodic Institute:

“Birds are messengers of rapid environmental change, in this case reflecting changes in one of the most-visited national parks in the U.S.,” said Schoodic Institute data analyst Kyle Lima, who led the study. “We must pay attention to these changes and work intentionally with nature to adapt.”

Both resident and migratory species have declined, including some of the most common birds, such as common eiders and long-tailed ducks. Of 162 species recorded during these winter counts, 42 species decreased in abundance.

While there are now fewer birds overall, 33 species showed increasing abundance. “Birds are shifting their home ranges and chasing their suitable habitat as conditions change,” said Lima. “Species that are common to our south are becoming more common here. For example, the northern cardinal has been increasing steadily since the 1970s, when they were uncommon.”

“The birds at Acadia are extremely important both ecologically and as an amazing visitor experience,” said Acadia National Park biologist Bik Wheeler. “This study shows us that regional and continental declines are happening at a local level at Acadia. We need to identify causes for these declines and pursue opportunities for stewardship, because there is good news here, too. Bird stewardship works, and we can turn population trends around. For example, the peregrine falcon was once eliminated from the park and now Acadia is home to a productive population.”

Peregrine falcons, though not typically winter residents, are one of the species exhibiting an increasing trend in the Christmas Bird Count study, first appearing in 1992.

Schoodic Institute scientists Nick Fisichelli, Seth Benz and Peter Nelson also contributed to the new analysis, as well as long-time Christmas Bird Count compiler and retired National Park Service ranger Bill Townsend.

Read the full story from Schoodic Institute: New research shows dramatic declines in Acadia National Park winter bird populations

Additional coverage:

Podcast: Birding Changes At Acadia – via National Parks Traveler

Winter bird numbers are declining rapidly in Acadia National Park, study shows – via Maine Public