Acadia is Changing, and Change is Messy

July 29th, 2024

July 29th, 2024

BY AMANDA POLLOCK AND CATHERINE SCHMITT

Acadia National Park is still showing the impacts of multiple storms this past winter.

It’s true, storms impact Acadia’s landscape every year; ecosystems continually change and evolve over time.

During a typical storm with strong wind, trees come down in the park’s forests. Those downed trees keep ecosystems functioning (and provide a welcome habitat for fungi and amphibians and a host of other wildlife).

But this year’s winter storms were different.

The first, on December 18, 2023, brought wind and rain that set the tone for the rest of the season. The Rainwise monitoring station on Cadillac Mountain recorded more than two inches of rain and wind gusts of 55 miles per hour (mph) throughout the day.

With hurricane-force winds and waves of 30 feet, two more storms came in January. Both arrived during high tides, inundating the shoreline with the highest water levels recorded in Bar Harbor since the tide gauge was installed and monitoring began in 1947.

Then came another storm in March, washing out Seawall and other roads (again) and eroding Sand Beach (again).

Waves crash on the stairs at Sand Beach during high tide the day after a damaging winter storm on January 14, 2024. The storm eroded a significant portion of Sand Beach. Photo by Julia Walker Thomas/Friends of Acadia

In the Seawall Campground and Seawall Picnic Area, there were more than 700 downed trees.

Sand Beach and Little Hunters Beach experienced significant erosion and sloughing near visitor access points, which park staff continue to monitor. About 1,000 feet of the historic Ocean Path was destroyed. The foundation of the Blue Duck Ships Store next to the Islesford Historical Museum was undermined, as was a section of Schoodic Loop Road.

In most places, these changes require little or no immediate management response. But park teams are monitoring areas for impacts that might require action, including the spread of invasive species into disturbed areas and erosion that might threaten trails or roads.

It will take us several years to truly understand the impacts these storms have had on park landscapes.

Rocks tossed up by waves during January 2024 storms cover an area at Seawall Picnic Area. (Photo by Catherine Schmitt/Schoodic Institute)

Protecting resources, ensuring visitor safety, and providing a fulfilling visitor experience are always on the minds of those with the National Park Service (NPS).

As soon as it was safe to do so, park teams started to clean up storm damage so that roads, trails, and carriage roads could open as soon as possible. It quickly became evident that we would be unable to fix all the storm damage on our own.

The National Park Service’s Emergency Incident Management Team and Arborist Incident Response Team came to the park in February. This team consists of rangers from all over the country who are specifically trained to support emergency response and recovery efforts. By working alongside Acadia’s own cutting crew, within a week they had cleared all the downed trees in the Seawall Campground and Seawall Picnic Area.

The outpouring of support from our local community was humbling.

Friends of Acadia jumped at the chance to support the park, raising $200K in a storm restoration challenge to help prepare the park for another busy summer season. Volunteers worked to remove debris along Schoodic Loop Road, Otter Creek Causeway, and Seawall Picnic Area. Volunteers will continue to assist with storm damage clean-up this summer through a stewardship program led by Friends of Acadia.

We also knew that it would be critical to repair one of our most used trails in the park: Ocean Path. Thanks to the generous support of Friends of Acadia, we were able to make temporary repairs and safely open Ocean Path for the summer.

Equipment proves essential during work on Ocean Path in spring 2024 following intense winter storms. (Photo by Eliza Worrick/Friends of Acadia)

We’ve made progress, but we still have a long way to go.

The park has submitted storm damage assessments to the NPS Washington office, and those assessments are now under review. Park staff have repaired and stabilized some areas of the park with the resources we have available.

We’ve also begun restoring and monitoring park ecosystems, including mapping and measuring erosion at Sand Beach and Frazer Point, restoring summit vegetation to reduce runoff and erosion, and continuing king tide monitoring to detect how the re-shaped shoreline will influence high tide water levels.

Now, we can start looking toward long-term alternatives for adaptation.

We expect that extreme weather events, like this winter’s storms, will occur more frequently and with more intensity, given the rapid pace of climate change.

Park teams want to make sure that when we invest in the rehabilitation of an ecosystem or the reconstruction of a trail, those resources will last for decades to come. Park staff take the responsibility for spending taxpayer dollars or private donations very seriously. No one wants to waste money.

To make informed, purposeful, and strategic choices despite a rapidly changing climate, Acadia National Park staff use a framework known as Resist-Accept-Direct (RAD). This means that, based on the best available science, we can choose to resist change (put things back the way they were), accept change (allow change to happen and accommodate it), or direct change (actively steer inevitable changes toward a new, desirable condition).

Decisions about whether to resist, accept, or direct change are not simple, and the options aren’t mutually exclusive. We adapt our planning and responses as we gain new information.

Interdisciplinary groups of park staff have begun preliminary RAD-based analyses. Each subject matter expert approaches challenges differently, and they often have different and sometimes competing priorities.

For example, when looking for a long-term solution for Ocean Path, our trail crew’s priority might be to harden the trail to resist any potential future storm impact, while our cultural resource manager likely wants to make sure that the historic trail, which is listed on the National Register, retains its historic integrity. Our biologists might want to make sure that any changes made to the trail won’t negatively affect the plants or animals that live around it.

All these perspectives are considered when making management decisions about Acadia’s future.

The park is going to be dealing with the ramifications of the most recent winter storms for years. However, we find solace in the reality that the lands now called Acadia have been here for thousands of years and will be here for thousands more.

With our continued stewardship, the National Park Service’s mission of preserving and protecting Acadia’s natural and cultural resources for future generations will endure.

AMANDA POLLOCK is the Public Affairs Officer at Acadia National Park. CATHERINE SCHMITT is the Science Communication Specialist at Schoodic Institute.

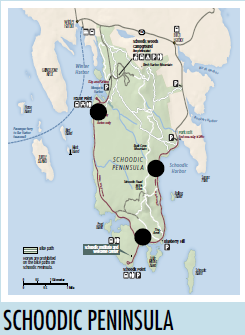

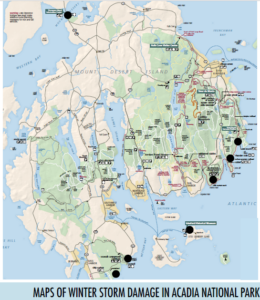

SCHOODIC POINT Waves overtopped the east side of the Schoodic Loop Road, flooding back-barrier wetlands and moving cobble beaches and coping stones onto and across the road. Trees were blown down and debris washed up on shore. Frazer Point Picnic Area was flooded.

THOMPSON ISLAND The picnic area was flooded and trees were broken and blown down.

SAND BEACH The January storms eroded the beach and dunes, and uncovered the Tay, a shipwrecked Canadian lumber schooner, which had been buried at the base of the dune. Erosion caused by multiple storms, combined with downed trees and precipitation infiltrating from above, led to unstable conditions and collapse of the bluff on the west side of the beach.

OCEAN PATH & OTTER POINT More than 1,000 feet of trail washed out, and many trees blown down.

OTTER CREEK Storm surge overtopped the causeway and receding waters left behind debris, driftwood, and broken trees.

SEAWALL CAMPGROUND AND PICNIC AREA Storm surge pushed the seawall inland and washed out the road, while wind blew down many trees in the campground and picnic area.

WONDERLAND Storm surge pushed the beach into the trees, wind blew down trees, and waves breached the eastern narrow part of the beach.

SHIP HARBOR Wave action broke apart a section of bog walk (and carried it to Seawall) and winds tore an information wayside from its metal base and tossed it into the woods.

LITTLE HUNTERS BEACH The high storm surge ripped away a portion of the wooden stairs leading to the beach from Park Loop Road.

LITTLE CRANBERRY ISLAND Wind tore the siding from the Blue Duck, a former ship’s chandlery built in 1853 that currently serves as home to Islesford Boatworks, and waves undermined the building’s foundation.

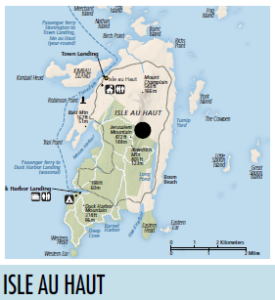

ISLE AU HAUT The National Weather Service reported a wind gust of 95 miles per hour on January 10.