Point of View: Managing Acadia’s Vistas

Vista management is a mingling of landscape management and artistry.

August 11th, 2025

Vista management is a mingling of landscape management and artistry.

August 11th, 2025

BY SHANNON BRYAN

Through the trees along the Eagle Lake Carriage Road, summer hikers and bike riders can spy the early morning sun reflecting hues of pink and orange across the water. This is vista No. 65.

Farther south, on the Jordan-Sargent Mountain Road, visitors are treated to open views across Jordan Pond toward Pemetic Mountain and beyond, the landscape diving and rising back up with relative drama from shoreline to ridgeline. This is vista No. 101.

These are views that prompt people to stop, mid-ride or mid-stride, to marvel. Acadia National Park has heaps of carriage road vistas like this: 182 of them, in fact, along 45 miles of carriage roads, according to the park’s Vista Management Plan for the Historic Carriage Road System. The auto roads boast another 69 historic vistas.

The most recent edition of the Vista Management Plan, published in 2023 by the Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, is a guidebook for maintenance that honors the historic intent of Acadia’s views and offers guidance for their futures.

Like swept-back curtains, some vistas reveal broad views of calm pond waters, a huddle of mountains, or the Atlantic Ocean stretching out to the horizon. Others subtly showcase the rustic stonework of a granite bridge or the wind-waving grasses and wildflowers in a meadow.

“When you think of ‘vista,’ you’re thinking ‘I’m up high looking out at a sweeping landscape.’ But there are certain vistas that are of a smaller wetland and a specific species of plant,” said Emily Owens, laborer at Acadia National Park.

Eagle Lake’s vista No. 65, which stretches 692 feet along the carriage road, might not even register to visitors as a vista. But a closer look reveals a delicate thinning of trees, allowing visitors that prolonged peek onto the lake.

Also less obvious: these vistas, as naturally occurring as they feel, require maintenance.

“The carriage road vistas were all intentionally designed,” said Gail Gladstone, cultural resource program manager at Acadia. “But because it’s landscape, it’s dynamic. It changes. It needs to be maintained, or it goes away.”

This winter, Owens and Alex Fetgatter, motor vehicle operator at Acadia, began an assessment of Acadia’s carriage road vistas to evaluate how those vistas are faring. They dove into vista history and the Vista Management Plan and gleaned a good deal about the nuances of Acadia’s landscape and the people whose visions shaped these particular views.

They also learned that each view has its own unique contours; its own diversity of flowers, shrubs, and trees; and its own singular outlook. Getting to know them means getting to know them one by one. As Owens said, “every vista is its own conversation.”

Vista views from the Witch Hole Pond Carriage Road, overlooking part of Witch Hole Pond. (Rhiannon Johnston/Friends of Acadia)

Most of Acadia’s carriage road vistas were designed in the 1920s and ’30s in tandem with the carriage roads by John D. Rockefeller Jr. and his team of local engineers, architects, and noted landscape architect Beatrix Farrand. He worked with Farrand for nearly 15 years to tailor the vegetation to highlight what he considered to be some of the most beautiful views in the world.

“Farrand valued views of the island’s natural features and took care to ensure that nothing of interest would escape the attention of those enjoying a ride in a carriage,” the management plan notes, adding that vistas were designed “for the height of the rider as well as for the pedestrian.”

With great care to maintain a natural aesthetic, vista edges were artfully blended with sloping transitions between open views and robust forest. Plantings were selectively chosen. Rockefeller’s appreciation for Farrand’s time and talent are

reflected in his letters to her:

“This is just a note to tell you how pleased I am with the planting in so far as I have seen it. You cannot know what a relief it is to me to have you giving attention to these matters for it had become quite a burden to me to try to keep up with them on all the roads. Then, too, what you do is so much better done than anything I could do.” – Letter from Rockefeller to Farrand in the summer of 1931.

Rockefeller funded maintenance of the vistas until his death in 1960. Over the next few decades, though, with the park managing multiple priorities and maintenance funds lacking, the vistas became overgrown.

A cyclist rides down the Upper Mountain Carriage Road down from Sargent Mountain. (Rhiannon Johnston/Friends of Acadia)

In the late 1980s, resource studies and park management plans recognized the historical importance of the carriage road system—

vistas included. And so, in 1994, Acadia National Park Arborist Jeff Grey was tasked with “transforming the existing carriage road vistas into what [he] felt best represented the intention of Mr. Rockefeller’s design for Acadia’s scenic views,” as he wrote in his

foreword in the Vista Management Plan.

Grey, who also enjoyed sculpting and drawing, was thrilled to take on the project. “I’m an artist,” he told the Acadia on My Mind blog in 2015. “This fulfills some of my talents.”

With guidance from Acadia’s resource managers and expertise from University of Maine’s forestry camp, among many others, Grey

and his crew set to rehabilitating Acadia’s carriage road vistas.

By 2005, the first 100 vistas were complete. Grey left Acadia for several years, but when he returned in 2012, he picked up where

he left off, finishing the remainder by 2018. This work was funded by a mix of entrance fee dollars, cyclic maintenance funds and other federal appropriations, as well as funds from Friends of Acadia. Volunteers also supported the effort.

“We depended heavily on the FOA [Youth Conservation Corps] crew and the FOA volunteers to assist in bringing cut material up

to the roadside for disbursal,” Grey wrote in a 2014 carriage road report.

The years-long efforts by Grey and others revitalized the park’s carriage road vistas and added a wealth of information to the

future vista-management playbooks.

Arborist Jeff Gray (left) and the vista management team in 2017. (NPS photo)

This past winter, Owens asked if she could dig into the Vista Management Plan and begin assessing the current state of at least some of the park’s views. Due to stretched resources at Acadia, the park’s vistas have been minimally managed since 2018, when Jeff Grey retired.

While undertaking them all would likely be a multi-year effort, Owens wondered what might be possible more immediately, and how they could plan for the next several years or more. “Every summer we do one section [of carriage road tree work], so it makes

sense that this would be part of that, section by section.”

The work relies heavily on the knowledge of park staff and the carriage roads’ original designers who came before her. It also requires trekking out to every vista and getting acquainted with its singular charm.

“It’s so wild how uniquely they were designed,” Owens said. “They were designed with someone who was standing right there

deciding why this was relevant, which makes it hard nowadays to do these big umbrella projects. You have to go out there and look

at each one and then plan that specifically.”

Emily Owens and Alex Fetgatter review the Vista Management Plan while looking at vista No. 40A on the north end of Eagle Lake. They’re also using digital tools, including ArcGIS, an interactive map that displays spatial data about a geographic location, including structures, roads, drainage

systems, and elevation. They view that data on a large tablet they bring into the field as they trek vista to vista, taking a slew of notes. (Julia Walker Thomas/Friends of Acadia)

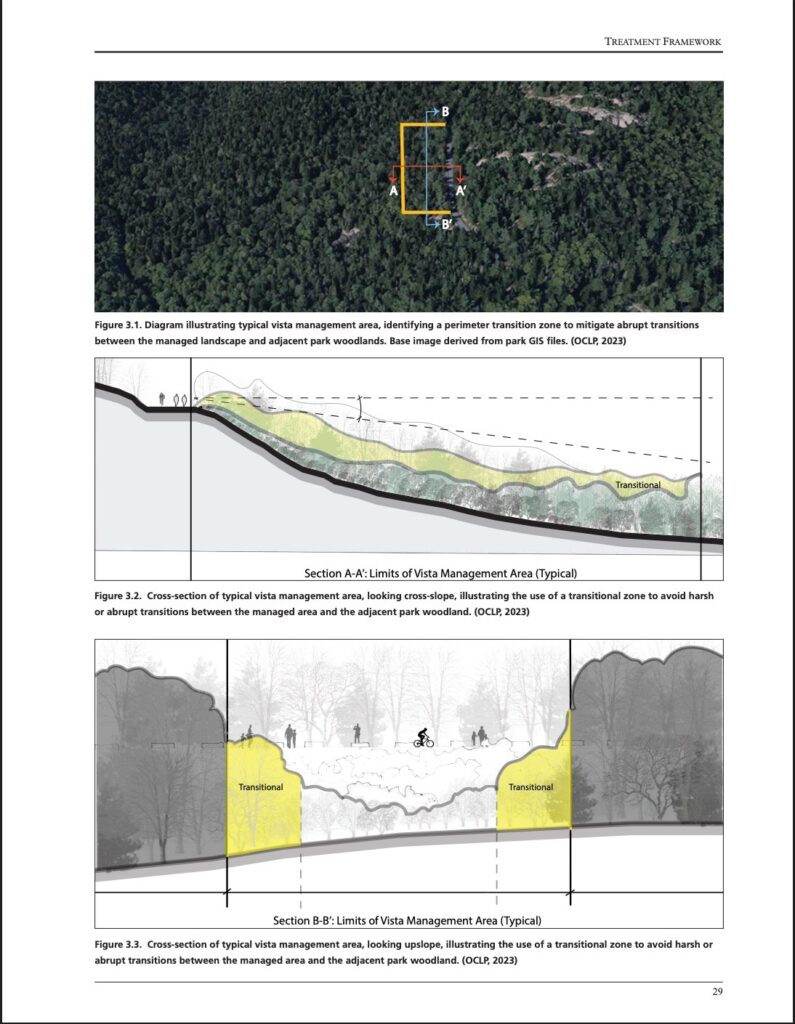

Page 29 of the Olmstead Center for Landscape Preservation’s Vista Management Plan.

The 2023 Vista Management Plan includes 182 vistas (the exact number of vistas has changed since Rockefeller’s time, as views were combined or created). Each vista is detailed out with maps and latitude/longitude coordinates, a description of the intended view, and images taken at the vista’s right, left, and center.

Descriptions of previous management work are included, as are recommendations for maintaining that vista into the future.

“The subject of CRV 65 was, ‘First view across lake to Cadillac and south to the Bubbles. [Beatrix] Farrand remarked on beauty

of view. Dense vegetation.’” A sticky note from 2013 describes the treatment for vista No. 65as, “Thin and control evergreen understory, remove hardwood and softwood poles. Prune oaks and promote huckleberry.”

Documentation like this removes much of the guesswork Arborist Jeff Grey faced in the ‘90s. But there’s still much to interpret.

“You can’t freeze the landscape in time,” said Gladstone. “What is maintained is the character of that vista. The vista plan that Olmsted put together identifies those important features. Then people like Emily and Alex can use their own artistic abilities and figure out how to achieve that ephemeral quality of a view.”

And the work is done in close collaboration with multiple park departments.

“We’ve got resource management thinking about the visitor experience and history. We’ve got biologists thinking about invasive species management,” said Owens. And they’re regularly in conversation with Gladstone, who was heavily involved in the Olmsted Center’s work to document vista history and develop a management plan.

“We’re not just making the view for people,” said Owens. “We’re attempting to have a holistic approach to make sure we’re not losing anything else by cutting some trees, and we’re not harming our already fragile ecosystem.”

As they evaluate, they’re identifying low-hanging fruit—vistas where the understory needs a trim, small trees and shrubs can be removed relatively easily, or limbs from larger trees can be taken down. As of mid-July, with the help of summer interns, Owens has assessed 80 vistas.

And vista work is well underway, supported by hardworking volunteers from Friends of Acadia’s drop-in stewardship program.

“I think we’re going to be able to finish the assessment this year and get more work done with the volunteers,” said Owens. She’s impressed with how much is being accomplished this season but is also looking to the future.

“We’re thinking five years out, 10 years out,” said Owens. “If we get the monitoring done, these could be projects that have longerlasting impact.”

Emily Owens, laborer in Acadia National Park. (Julia Walker Thomas/Friends of Acadia)

“The true craft of vista management is making it look like you weren’t there,” said Fetgatter, who was a member of Acadia’s vegetation crew during Jeff Grey’s tenure and helped rehab some of the carriage road vistas.

“We’re trying to do it in a way that is as unobtrusive as possible, make it seem like it happened naturally. Sometimes [we] keep that big tree in the view, because it gives a frame of reference,” Fetgatter said. “You have the foreground, the middle ground, and you have the mountain way in the distance. The value is enhanced.”

It’s the same artful thinking Farrand, Rockefeller, and Grey brought to Acadia’s vistas. Fetgatter’s favorite: Gilmore Meadow (a.k.a. vista No. 106A). “It seems to be one of the more remote areas of the carriage roads.

You’ve got to hike or bike quite a way,” he said. “You don’t see as many people, and you get a really nice view of the meadow and the mountains, maybe see some beaver activity. It’s a place I feel I can sit for a long time.”

That blend of artistry and landscape management is something Jeff Grey wrote about in his foreword in the Vista Management Plan, calling them “two long-standing passions of mine.”

Owens agrees: “You are painting a view for the visitor.”

Vista views of the North and South Bubble Mountain, overlooking Jordan Pond from the Eagle/Jordan Carriage Road. (Rhiannon Johnston/Friends of Acadia)

SHANNON BRYAN is Friends of Acadia’s Content and Website Manager.