Apples of Acadia

Conjuring Forgotten Agricultural Landscapes

May 30th, 2013

Conjuring Forgotten Agricultural Landscapes

May 30th, 2013

By Rebecca Cole-Will, Todd Little-Siebold, and David Manski

Downeast Maine was home to thousands of small, hardscrabble farms from the late eighteenth century forward. This is hard to imagine today in places like Mount Desert Island, where past agricultural landscapes have been replaced by alder, white pine, and spruce thickets for many decades. Land painstakingly wrested from the forest with fire and axe by generations of settlers beginning in the seventeenth century has quickly, inexorably returned to forest. In this area, farming, as measured by the number of farmers and acres of land, has been in decline since the 1860s, and there is precious little left save foundations of farmhouses or barns and grown up remnants of the original hayfields.

Downeast Maine was home to thousands of small, hardscrabble farms from the late eighteenth century forward. This is hard to imagine today in places like Mount Desert Island, where past agricultural landscapes have been replaced by alder, white pine, and spruce thickets for many decades. Land painstakingly wrested from the forest with fire and axe by generations of settlers beginning in the seventeenth century has quickly, inexorably returned to forest. In this area, farming, as measured by the number of farmers and acres of land, has been in decline since the 1860s, and there is precious little left save foundations of farmhouses or barns and grown up remnants of the original hayfields.

Most visitors to Acadia probably don’t realize that the stunning landscape they love to hike, drive, and bike was previously dominated by farms. Today, Acadia National Park is best known for its natural resource values. However, the park’s rich history, including the early agricultural period, is equally of importance to protect and interpret. While the National Park Service does actively manage the Carroll Homestead and the original settlement on Baker Island there are many other valuable historic farm-related resources in the park that are not as well preserved or as well known.

Incredibly, one important legacy of this agricultural past sits hidden in forests, along roadsides, or in old fields throughout the park and the Downeast region.

They are the old apple trees and relict orchards that survive here and there. They are a direct connection to the small, diversified farms that were the undergirding of the local communities along with fishing and lumbering. They are a living testament to a different world and they represent a generally unknown source of biodiversity.

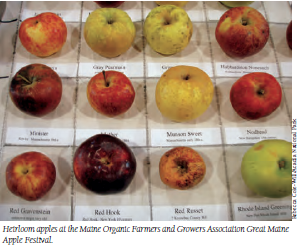

As one begins to explore the history of apples in Maine most people are startled to learn that there were more than ten thousand varieties of apples being grown in the state in 1850. The people of Maine had not just the familiar Macintosh, Cortland, Fuji, and the ten or so others commercially available today. They had thousands of varieties from which to choose—some for fresh eating, others for pie or sauce, and still others used primarily for making hard cider. Names like Nodhead, Bare-limbed Greening, Blue Permain, Stone Sweeting, or Marlboro offer plenty to feed our imaginations.

How did they taste? What did they look like? Where did they go?

In 1885 Charles Atkins of Bucksport reported that in his area, “In old orchards you will find Yellow Bellflower, Kilham Hill, Nodhead, Blue Permain, Mathew Stripe (or Martha Stripe) a very sour winter apple; an old fashioned Russet something like a Roxbury, Hunt Russet, Stone Sweet (a hardy winter sort), Queen’s Pocket (winter), Lyscom (September, also known as Mathew, or Martha Stripe), Hightop Sweeting, Williams’ Favorite, Golden Russet (early), Leland’s Golden Pippin, Bell’s Early, and a long list of obscure sorts, mostly unnamed.” He quickly added a caveat: “I speak only for Bucksport and other towns adjoining, on the river about its mouth. In the interior of the county they might tell a different story.”

This diversity came from thousands of farmers finding promising seedlings along the edges of their fields and stone walls, which they named and then passed along to others.

Settlers also brought their favorite varieties with them as they established themselves in northern New England or Southern New France (and maybe even at

Basque fishing stations on offshore islands). Because each seed in every apple is genetically unique, varieties can only be propagated by grafting a scion, or a small piece of a branch from a named variety, onto your own tree.

Around 1830, a boom in orcharding in the United States gave rise to thousands of named varieties in Maine alone. Some were known only within one town, like the Marlboro from Lamoine, while others are nationally famous, such as the Black Oxford from Paris, Maine. These commercially grown varieties were shipped away, with hundreds of thousands of barrels being shipped to Liverpool alone from Maine. The scattered relict orchards we see today are the descendants of that commercial boom.

Maine may have one of the highest levels of apple diversity in North America because of its history. At the frontier between French and British colonial holdings, both French and English colonists brought their varieties with them as they settled Maine in different waves. Then the commercial boom contributed to the explosion of apple varieties in the early state of Maine. Finally, as the family farm declined in northern New England after the Civil War, the orchards, too, were abandoned. But many still may hold the genetic diversity of their history. In other areas that remained commercially active into the mid-twentieth century, orchards were transformed into production units that typically grew only three to four varieties, rather than the dozen or so common in an old Maine orchard.

So too, there are many old orchards on Mount Desert Island and within Acadia National Park that are part of this story.

Researchers from College of the Atlantic, park resource managers, and heirloom apple expert John Bunker from the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association (MOFGA), have begun research to locate the old orchards, identify and document fruit varieties, and connect the history of apples to the larger agricultural history of the island and state.

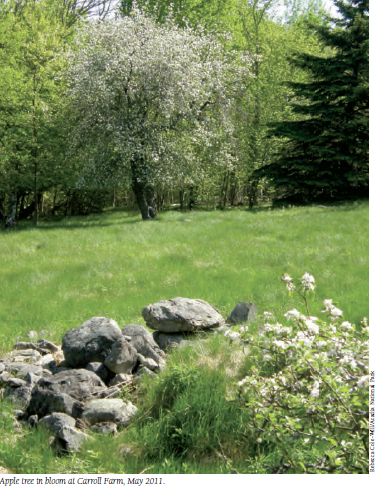

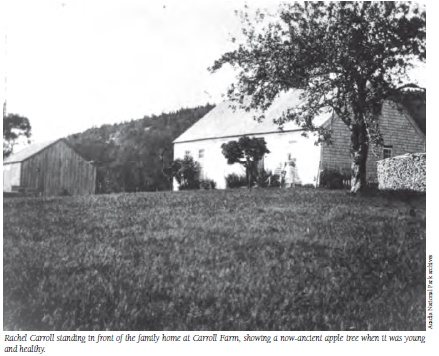

Early findings have revealed, for example, that the Carroll Homestead in Southwest Harbor had a diverse orchard in the 1800s.

Luckily, it was documented by interviews with family members who remember the rare Jacob Sweet apple grown there. On Bakers Island, apple trees probably planted by the Gilley and Stanley families who settled the island in the early 1800s still bear fruit. And on the slopes of Cadillac Mountain, just a few steps off the Park Loop Road, there is an abandoned orchard with over 50 trees. One can imagine that this commercial orchard supplied the many hotels and summer homes of the first wave of summer visitors to the island.

In 2009, Catharina Wehlburg, an intern from Germany, spent six weeks in Acadia working on this project. She interviewed park staff knowledgeable about the locations of apple trees, worked with the park’s cultural resources specialist to research the history of historic sites in the park, and assisted COA GIS students to map the Cadillac orchard. The NPS and COA are now discussing small projects to help protect that orchard by pruning dead wood to promote healthy growth and minimally cutting back surrounding vegetation that is crowding out the fruit trees.

This work might be done in partnership with COA students and volunteers interested in learning orchard history and orchard management and pruning.

Other small projects have helped old trees. Volunteers pruned Northern Spy (also known as Northern pie apple) trees near Sand Beach that were part of the agricultural fields of the Satterlee compound there. The trees were planted by Louisa Morgan Satterlee, the fabulously wealthy daughter of J. Pierpont Morgan.

The orchard survived the great fire of 1947, unlike much of the rest of the Satterlee’s many buildings and gardens. On Baker Island, the park’s fire management program has begun a project to protect the standing buildings and surrounding fields from fire. Careful work to remove large spruce trees around the buildings will also help the last vestiges of orchards to compete against the encroaching forest.

Across the National Park system, park managers have come to recognize the importance of agricultural landscapes and orchards as important cultural landscapes and sources of biodiversity. More than 130 national park areas contain fruit trees greater than 50 years old.

Their significance is elegantly documented in a recent publication, Fruitful Legacy: A Historic Context of Orchards in the United States by Susan Dolan. Orchards in national parks are important because they are touchstones for the history that the parks preserve, and protect fruit varieties that are no longer commercially available. For example, at Manzanar National Historic Site, Japanese internees renovated apple and pear orchards abandoned in the 1920s. Mormon settlers studied the technology of irrigation from ancestral Pueblo sites to bring water to Capitol Reef. Today, the orchards there provide opportunities for park visitors to harvest fresh peaches, apples, and pears.

Dolan points out that “Orchards have always been a reflection of societal values and economic and technological realities, and they have been made to fit the changing realities. The many historic orchards in national parks and elsewhere are cultural landscapes that memorialize these events, trends, and eras in American history. As we preserve orchards that are 50 years of age or older and that retain significance and physical integrity, their cultural resource value will continue to grow in importance. Genetic biodiversity conservation combines with visitor education as potential societal benefits.”

The College of the Atlantic has launched an effort to renovate the three old orchard blocks contained in its Beech Hill Farm, which were parts of three different farms there in the nineteenth century. Three years of pruning and care have lead to a revitalization of the twenty or so varieties surviving there. The varieties identified include Baldwins, Saint Lawrence, Pewakee, Famuese, King of Tompkins County, Pound Sweet, Greenings, and several others. The composition of the orchards indicate that they were planted for the late-nineteenth century trade with England. Using this as the nucleus, the College is beginning to plan and undertake fundraising for a Downeast Heirloom Orchard that would include all of the apples, pears, and other fruit that were commonly grown during the region’s agricultural heyday, as well as a wide range of unusual and less known varieties.

Framed as a community orchard, it would be a place for school kids, visitors, and community members to learn about the rich agricultural history of the region through fruit.

As one looks out across Mount Desert Island from any mountaintop it is difficult to conjure a landscape dotted with small farms, much less of orchards. Imagine Bar Harbor, Northeast Harbor, or Otter Creek as farming communities. Farming declined on MDI as agricultural markets, out-migration, and transportation turned the tide against small diversified farms and led to the abandonment of whole areas of the island that had been farms. In fact, lands that would become the heart of the park, geographically, became available for purchase because of the history of farming (and lumbering) in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The old farmhouses are prized but the landscapes they were linked to have been devoured by development or obscured by the regeneration of forests. As students delve into census records or volunteers prune old apple trees at the Satterlee orchard, first steps are being taken to reconnect to the lost landscapes of the past, which can both inspire future generations with their beauty and fruit and preserve the last fragments of the region’s rich agricultural past.

If you have information about the location or history of apple or other fruit trees in the park and on MDI, please share your knowledge with Rebecca Cole-Will (rebecca_cole-will@nps.gov) or with Todd Little-Siebold (tlittle@coa.edu).

REBECCA COLE-WILL is the cultural resources program manager at Acadia National Park, and an archaeologist specializing in pre-European contact archaeology of New England and the Arctic.

TODD LITTLE-SIEBOLD is professor of history and Latin American studies at College of the Atlantic.

DAVID MANSKI is the chief of resource management at Acadia National Park.

Note: This story was originally published in the spring 2013 issue of the Friends of Acadia journal