Centennial Milestones

1924 turned out to be quite a year for the park and the genesis of a few notable area institutions.

November 12th, 2024

1924 turned out to be quite a year for the park and the genesis of a few notable area institutions.

November 12th, 2024

BY RONALD H. EPP

The first full assessment of “Dorr’s Park” was published in 1924, eight years after the establishment of Sieur de Monts National Monument and five years since its elevation to Lafayette National Park.

“An Analysis of Lafayette National Park” remained underappreciated over the decades, although it received an uplifting review in The New York Times. It was authored by the nationally renowned New York journalist, editor, and publisher Robert Sterling Yard (1861-1945). In 1915, Stephen Mather, assistant to the Interior Department Secretary, tasked Yard with directing the first national parks public relations campaign.

Yard’s impressive publication is one of four Mount Desert milestones from 1924 that deserve renewed attention.

World War I (1914-1918) disrupted adventure travel from America to Europe, creating an opportunity to promote the superlative natural wonders of our western states. To that end, during the war years Yard collected and distributed massive numbers of national park articles, pamphlets, photographs, statistics, and maps.

With Mather at his side, Yard repeatedly crisscrossed this territory, gathering firsthand park experience for his 260- page lavishly illustrated and eloquently written “National Park Portfolio.”

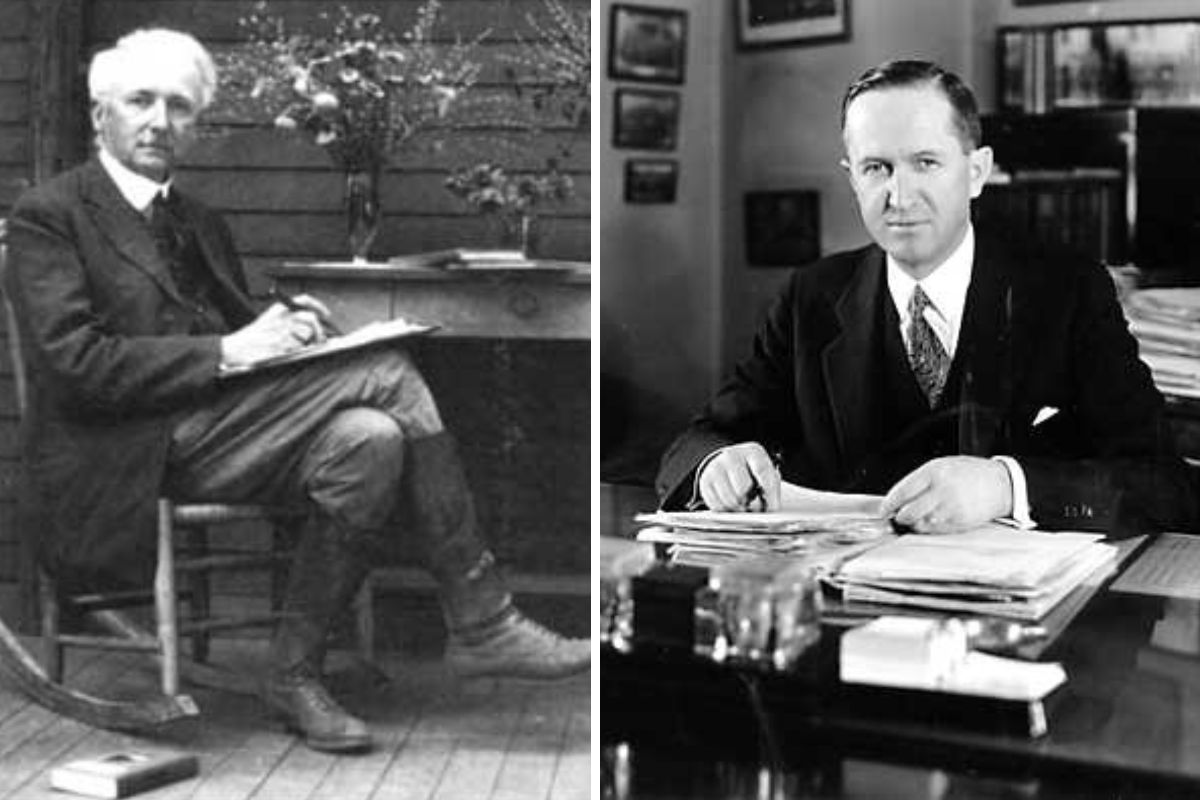

Left: Robert Sterling Yard. Right: Horace M. Albright. (Photo courtesy NPS)

This celebration of park landscapes and pristine wilderness was sent in a media blitz to 275,000 legislators, civic groups, and chambers of commerce immediately before passage of the National Park Service Organic Act of 1916, which established the National Park Service (NPS).

Yard, Mather, and NPS Assistant Director Horace M. Albright aggressively applied the “See America First” railway brand to the park service mission, targeting support from industry, politics, publishing, and land conservation leaders for the scant funds available during the war years.

formation of the National Parks Association in 1919 (it is today known as National Parks Conservation Association). As its executive secretary, Bob Yard led this nonprofit in publicizing and defending the National Park System.

It quickly became clear, however, that the National Parks Association was not just an NPS mouthpiece, as it argued against what it perceived as overzealous park service promotion of road development and motorized access.

Stephen Mather and Robert Sterling Yard, first and second from left, and Horace M. Albright, far right, during the 1915 dedication of Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado. (Photo courtesy NPS)

The most dramatic impact of these landscape threats arose when, in 1920, representatives of 12 western states formed the National Park Touring Association. They set in motion the National Park-to-Park Highway Tour, a 5,600-mile loop motorized excursion through nine national parks.

Capitalizing on his NPS/NPA experience, in 1923 Yard and his family vacationed in Southwest Harbor and later for 10 days at Dorr’s Oldfarm estate. There he was provided with nearly two dozen Sieur de Monts Publications written by scholars of wide renown on the cultural, historic, and natural distinctiveness of Mount Desert. From these, Yard expanded, unified, and composed “An Analysis of Lafayette National Park.”

The NPA Bulletin published his derivative article on “Gift Parks: the Coming National Parks Danger;’ which had appeared in the October 31, 1923 Bar Harbor Times. Yard claimed without reservation that east of the Mississippi the nation now possessed the “quite perfect” park. Lafayette National Park was his standard bearer park, an “American masterpiece.” Whereas Dorr argued in the Sieur de Monts Publications for federal acquisition of tracts of land known for their beauty and their proximity to important cultural centers, Yard was distressed by the rising support for eastern-park inclusion of sites that lacked comparable pristine scenic qualities.

His arguments to “protect the [NPS] trademark” were not well received by the NPS and so it is not surprising that a decade before his death Yard co-founded the Wilderness Society, further championing the merits of “unimpaired” public sanctuaries. This goal was also the foremost concern of those who challenged Dorr’s park management in the unprecedented March 1924 Interior Department hearings before Secretary Hubert Work.

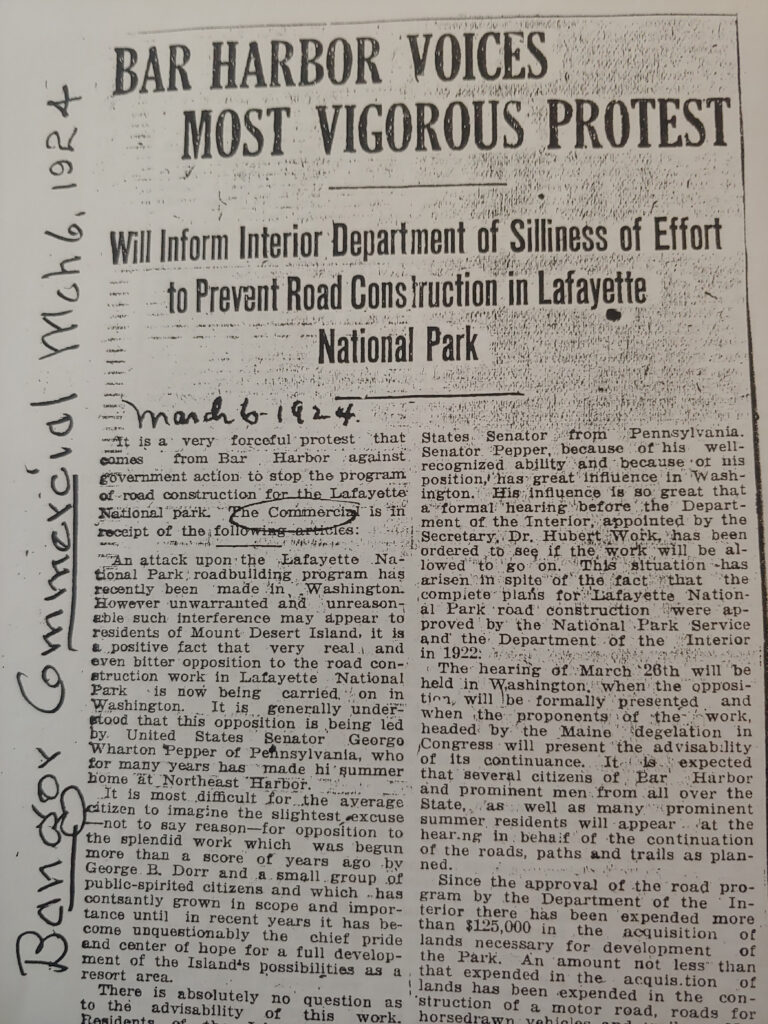

Protests surfaced in Northeast Harbor regarding alleged abuse in the development of the park’s motor and carriage roads. U.S. Senator and summer resident George Pepper fronted claims that the privacy of the wildest portions of the new park were being sacrificed by the ambitions of Dorr and John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Story in the March 26, 1925 Bangor Commercial reporting on the 1924 Washington road hearing before Interior Secretary H. Work.

In response, there was no shortage of prominent citizens who spoke on behalf of the work being done in the park. Dorr later explained that the effect of an inadequate defense would have “spelt disaster” for the park.

Most fortunately, during that summer of 1924, park inspection trips by Mather and Secretary Work authorized both road and carriage road development.

Before Secretary Work left the island, Dorr brought him to Brook End to meet New York surgeon Dr. Robert Abbe. There Abbe showed Work local indigenous stone artifacts that he thought might be the nucleus for a local museum.

This news of a local archaeological collection resonated with Work, who disclosed that the National Park Service had just received funding from the Laura Spellman Rockefeller Memorial to establish a museum for a similar park collection at Yellowstone.

Two years later, her son donated $15,000 for Lafayette National Park’s Museum of Stone Age Antiquities, which was dedicated in August 1928, just five months after Abbe’s death. In pioneering national park museums, Dorr and Abbe sought to expand the NPS mission into interdisciplinary public education.

Oldfarm (Photo courtesy NPS)

The final 1924 milestone took place a half mile from Oldfarm. In late spring, University of Maine students had been given permission to set up the rudiments of a biological research station. Dorr owned this 13-acre parcel but agreed with University of Maine president and geneticist Clarence Little, that scientific inquiry actually served both the university and the park.

Six months later Dorr wrote to Charles W. Eliot that he was already convinced that the lab “is destined to grow into one of [Mount Desert’s] most interesting and valuable features.”

Such belief was grounded in decisions made a decade earlier when Dorr and Abbe raised funds to purchase a 14.5-acre Salisbury Cove parcel to honor physician and novelist S. Weir Mitchell. In time, The Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory became that living memorial. Similarly, in memory of his parents, Dorr formally donated the parcel within view of Oldfarm as the foundation for the Jackson Laboratory.

Quite a year for the park and the institutions that it spawned.

Author’s note: This article reflects research undertaken since publication in 2016 of Epp’s “Creating Acadia National Park.” It aims at reviving interest in Yard’s 1924 publication and its reliance on the earlier studies that Dorr authored and edited. “An Analysis of Lafayette National Park” can be downloaded from the DigitalCommons at the University of Maine.

RONALD H. EPP is the author of “Creating Acadia National Park: The Biography of George Bucknam Dorr.”