Schoodic as Muse

Among the most painted places in Maine, Schoodic Point casts a mighty spell on artists.

January 4th, 2022

Among the most painted places in Maine, Schoodic Point casts a mighty spell on artists.

January 4th, 2022

The Wave, 1940-41 (oil on masonite) by Hartley, Marsden (1877-1943), Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts.

By CARL LITTLE

In the late 1930s, painter Chenoweth Hall and her partner Miriam Colwell, from Prospect Harbor, befriended Marsden Hartley, the renowned American Modernist who was living what turned out to be his final years in nearby Corea. Hall and Colwell told Hartley authority Gail Scott that whenever a storm was brewing on the coast, they would pick up the painter, who didn’t have a car, and drive him to Schoodic Point. He brought along no art supplies; he simply sat and watched as the waves leapt up over the rocks.

Hartley ended up painting several versions of the scene, each a vision of an ocean in turmoil. The most famous, The Wave, 1940-1941, earned a place in art historian and Mount Desert Island summer resident John Wilmerding’s book American Marine Painting. Wilmerding described Hartley’s wave as being “as substantial and monumental as a mountain.”

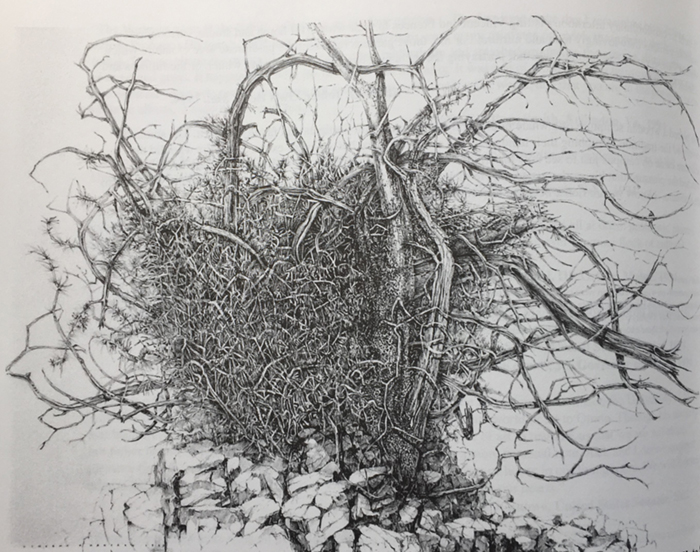

Top: Vincent Hartgen, Nor‘easter, Schoodic Point (Gnarled Juniper), 1992, pen and ink, University of Maine Museum of Art

Another Schoodic frequenter, artist Vincent Hartgen (1914-2002), found respite from academia on the point. When teaching took its toll—Hartgen ran the art department at the University of Maine in Orono—his wife Frances would chauffeur him to the coast where, sketchbook in hand, he would draw. His Schoodic drawings and watercolors are among his most brilliant.

Many artists before and after Hartley and Hartgen have found their muse at Schoodic. Indeed, when considering the most-painted spots in Maine, this Downeast eminence goes toe to toe with Monhegan, Stonington, Katahdin, and Portland Light.

Stockton Springs resident Sarah Faragher, who was brought up in Bar Harbor, spent quality time at the point as an Acadia National Park artist-in-residence in 2015. “Schoodic feels like a scouring-out place, where nature is still wide open and wild,” she writes. “I love to be there, out on what feels like the edge of everything, participating in nature.”

Faragher takes a stylized approach to Schoodic motifs, softening the rocks and crashing surf. She evokes the change of seasons in Migration Southwest of Schoodic where geese form irregular patterns in the sky as they fly over low-lying islands.

Joel Babb, who lives in East Sumner in western Maine, remembers first seeing Schoodic from a sailboat on a cruise from Southwest Harbor up the coast to Cross Island off Cutler. “It seemed beautiful and unspoiled, a gateway to an unexplored part of Maine,” he recalls.

Babb finally returned to paint the place in 2006, at the tail end of a camping/painting trip to Mount Desert Island. “I was exhausted,” he recalls, “but decided to spend a day at Schoodic before going home.” Glad was he of that decision: he created one of his finest plein air paintings, which led to a full-scale oil two years later.

That first painting took about five hours, but the time, Babb says, “seemed to pass in an instant.” Afterwards, lying on the rocks, looking at clouds passing overhead, listening to the water “working away,” he felt as if he were riding the granite ledge into the distances. To his eye, the rocks “seemed to be quarried neatly by natural forces and tilted against the perfection of the horizon.”

From her home in Jackson in Maine’s midcoast, Janice Anthony visited Schoodic a number of times over the years with her family, part of their explorations of wild places in the state. They were impressed by the huge tides, expanses of rock and the ever-present horizon. More recently, they stayed at the Schoodic Woods Campground, just a few weeks after it opened in September 2015.

Anthony’s feelings about Schoodic align with Faragher’s and Babb’s. She loves its sense of “limitless space, of moving air and restless water, of mists and reflections” and how the colors intensify at the end of the day. Most meaningful of all is “the eternal presence of the underlying rock, defiant against the ocean waves, sheer cliffs standing unperturbed, and cobblestones moving and adapting like living beings to the flow of water.”

Those cobblestones are featured in several paintings, their rounded shapes spread out like some marvelous glowing gift from the sea. Alert while traversing them, Anthony hears the voice of her geologist mother “pointing out a basalt dike running through the granite ledges and the rarest wildflowers along the shore.”

All three painters look forward to future Schoodic encounters. Anthony seeks “an unheard conversation between strong forces that existed before me and will continue without me” while Faragher hopes to continue the relationships she is building there “with the ledges, lichen, spruce trees, and ocean.”

Babb’s attraction to what he calls “the end of the world” lies in how “the order and structure of the earth ends at the edge of something great and different and disorderly”—and, he might have added, eminently paintable. The lure of Schoodic is strong and timeless.

CARL LITTLE of Somesville recently received the Lifetime Achievement Award for his art writing from the Dorothea and Leo Rabkin Foundation.

This article appeared in the Fall 2021 Acadia magazine.