For as long as she can remember, Marie Yarborough has been drawn to historical objects and the stories behind them.

“I’ve always loved museums,” said Yarborough, who grew up in Connecticut. “My grandmother used to take me to museums, and I have early memories of going to the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, so I always wanted to work in museums.”

Her first job, beyond babysitting and a paper route, was in a museum café.

“I thought, well, I can’t work in the museum because I’m not qualified because I’m a teenager, but I can work in the café. I was always really interested in museums and objects and the people who made them.”

That teenage café employee eventually made her way to college, and while browsing the course catalogue came across something new yet deeply familiar. “I opened the book and of course ‘A’ was first, and I saw ‘Anthropology,’ and I read the description and thought, ‘Oh my God, this is what I’ve wanted to study my whole life,’ although I didn’t even know that it existed! This is so amazing.”

Yarborough’s determination followed her to Acadia National Park, where she spent summers working at the Jordan Pond House to earn money during college. One day, during a drive along the Park Loop Road with a friend, she stumbled upon the Abbe Museum’s original, trailside location at Sieur de Monts. Intrigued by a museum nestled in a national park, Yarborough poked around and quickly decided, “I am going to work at this place. I called them up and said, ‘I waitress six days a week, but I have a day off, can I volunteer for you?’ and they said, ‘Sure!’”

Following that formative summer, Yarborough went back to college, then graduate school, where she eventually earned a master’s degree in American History. Her first job out of school? “I was the very first education coordinator at the Abbe Museum’s downtown Bar Harbor location.”

After spending many happy years at the Abbe, Yarborough and her family left Maine for a brief stint.

“We were trying to get back quickly because we missed Maine so much, and a job at Acadia opened in the interpretation division. They wanted someone that had a background in cultural anthropology and had an interest in and experience working with Native people and teaching about Native people and Northeastern Native American history, which of course I had.”

Yarborough landed the job, which began as a seasonal ranger position for the summer, but she was picked up for that winter and the following spring by the new Chief of Interpretation, Lynne Dominy, who had a background in working with Native people and Indigenous groups at other parks and wanted to bring that same collaboration to Acadia.

Marie Yarborough, Acadia National Park curator and cultural resources/interpretation liaison, stands among the historical archives at park headquarters. (Rhiannon Johnston/Friends of Acadia)

Eventually, Yarborough became the writer/editor for Acadia National Park, which included managing a major wayside exhibit (those signs you see installed along roadways providing context for a particular view) project stretching more than five years. As that project was winding down, a curator position in the William Otis Sawtelle Collections and Research Center became available. This job would allow her to work with objects and their histories once again, so she jumped at the opportunity to apply.

That was 10 years ago, and Marie is still thrilled by the archives daily. “People always ask me what my favorite object is here, and I always say I have a new favorite object every day;’ she said. “It really depends on when I learn something more about an object, or when I discover something exciting about it and learn its history.”

Seeing the collection in person, locked away in a climate-controlled facility at park headquarters among expanding shelves reminiscent of a college library, it’s easy to understand why choosing a favorite item is so difficult. The facility houses about 285,000 cataloged objects, along with archival collections that

reflect the history of Acadia.

“We have a wide depth and breadth of the types of objects and artifacts that we care for. We have objects made of wood, of metal. We have furniture. We have textiles. We have natural history specimens, which are important to mark and understand the science of Acadia over the past 100 years.”

Marie Yarborough opens a drawer filled with artifacts. (Rhiannon Johnston/Friends of Acadia)

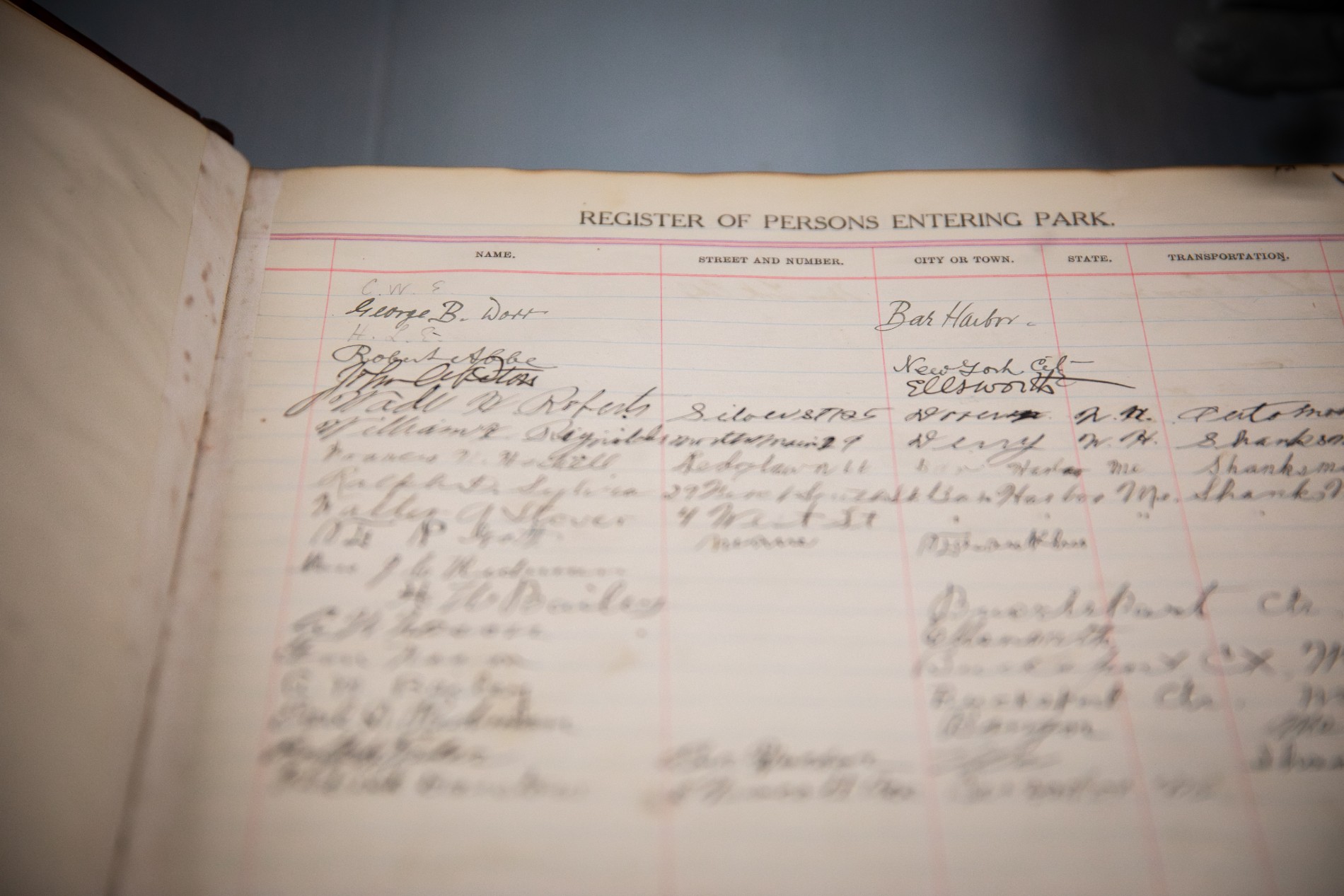

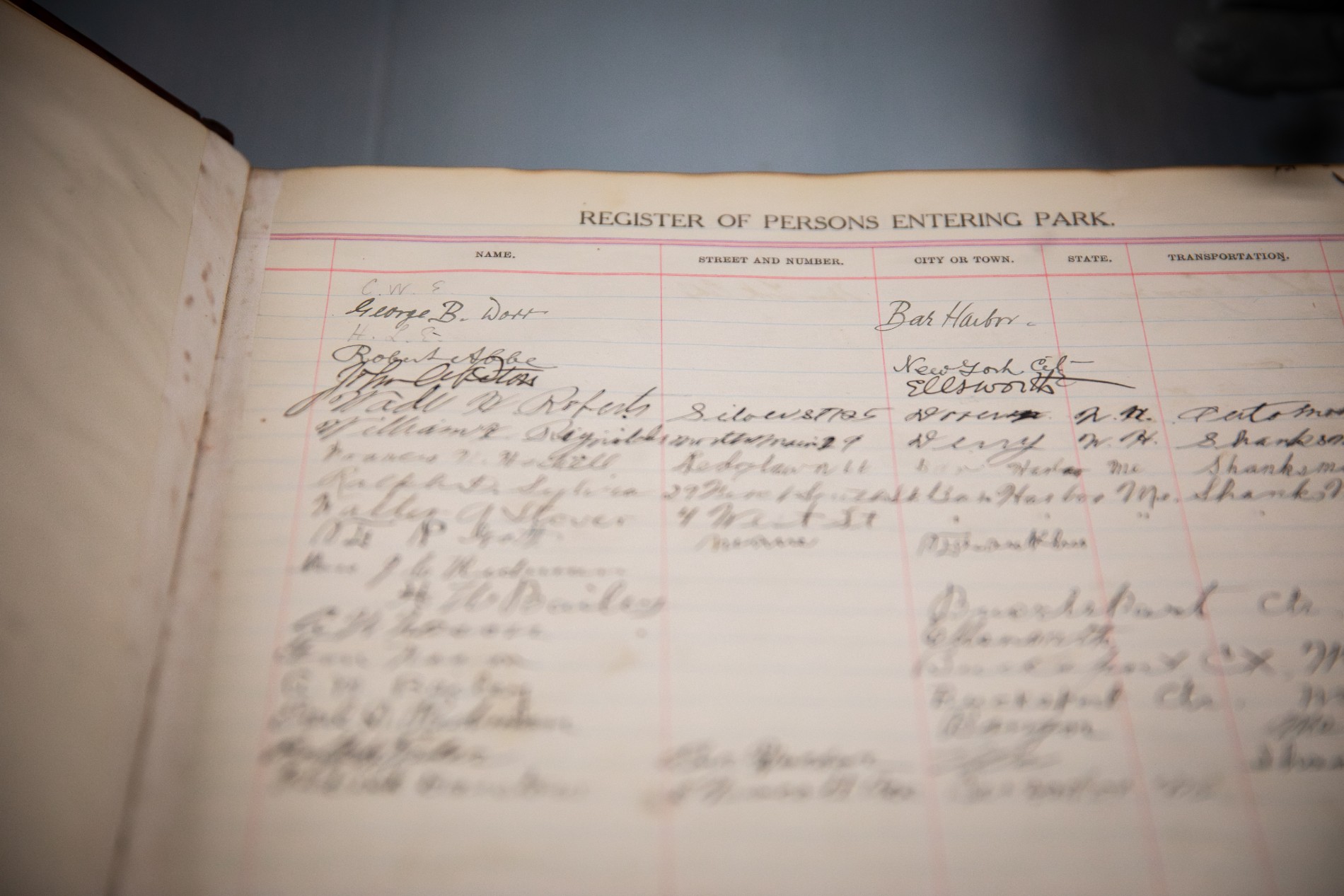

Register of visitors entering Lafayette National Park (which later became Acadia National Park)) from 1919. While one might assume that the first “visitor” would be George B. Dorr, it was one of the park ‘s other founders, Charles W. Eliot.

Taxidermized owls in a climate-controlled cabinet. (Julia Walker Thomas/Friends of Acadia)

“What makes any object important is not what it is, but rather what it means about the people who made it, or held it, or loved it, or cared for it, or saved it. And those are the kinds of stories that we, the National Park Service, want to tell people, and that’s why we’re here – to help people see themselves in the history of this country, specifically right here at Acadia National Park.”

To ensure that Acadia’s archives are truly the best place for an item, Yarborough has thoughtful but strict protocols for how, when, and if she can accept it.

LEFT: Early carriage road sign. This early hand-carved and hand-painted sign was likely built by John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s staff for the carriage roods surrounding the family’s estate in Seal Harbor, adjacent to where Rockefeller began carriage road construction for Acadia in 1917. In 2016, this sign hung in the Smithsonian as part of an exhibit on the history of the Rockefeller family’s legacy of philanthropy.

RIGHT TOP: Masonry samples from historic bridges and buildings across Acadia. “An important collection that we keep is samples of historic fabric of buildings and structures we maintain,” Yarborough explained. These are often studied during rehabilitation projects to ensure historical accuracy and consistency. “By preserving original samples of the historic materials, we can better preserve or rebuild what makes those buildings so special to begin with.”

RIGHT BOTTOM: Painting of “The Bubbles.” This painting was created by Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camp artist Hugh Hegh at the McFarland Hill camp in 1934. The artist gave the work to Solon Conner, the camp’s superintendent at the time. Solon Conner’s son, Theodore, donated the painting to Acadia in 2009.

Accessioning an item, the formal process of bringing it into a collection, comes with the obligation to keep the item in perpetuity. Marie works with a collections advisory committee comprised of other park staff and regional curators. Together they determine whether they have the resources to properly care for an item and if it fits within the scope of Acadia’s history. If a piece isn’t the right fit for Acadia’s archives, Yarborough usually knows where it might belong instead.

“We have this vast network of these other cultural institutions that maybe don’t have the [NPS] arrowhead hanging behind their desks, but they are filled with really passionate people who have really beautiful collections that are capturing these things in a way that’s different than us, and they have different ways that they can do that. They may have more flexibility, and maybe that’s the right place for those things, and that’s okay. That’s what we’re here for.”

This deep care and dedication to historical objects is clearly as important to Yarborough as an adult as it was to her when she was young. “There are pieces of history [in this collection] that belong to all of us. I never want to look back and say, ‘We have these things that used to be someplace else, in somebody else’s control, and we ruined them.’ I want to say, ‘We have these things, and we’ve done good by them,’ Because it’s not the objects, it’s really about the stories that they hold and the connections to the people whose lives they represent, or whose hands held them-that’s really what it’s all about.”

ELIZA WORRICK is Friends of Acadia’s Digital Marketing Manager.

Join

Join Donate

Donate Acadia National Park

Acadia National Park