A Look Back at the Acadia Youth Conservation Corps

July 25th, 2023

July 25th, 2023

BY LYNN FANTOM

In 1970, Congress approved a three-year pilot called the Youth Conservation Corps to employ teens, ages 14 to 18, in summer conservation jobs.

Acadia National Park was one of nine sites chosen and so began “the most outstanding program for boys and girls – ever,” according to Bob Chaplin, who served as what is today known as the Acadia Youth Conservation Corps (AYCC) head of environmental education. His passionate bias can be forgiven.

The new decade held promise, despite inflation and unemployment. The United States had ended its involvement in the Vietnam War. Congress passed the Endangered Species Act. And the Grateful Dead sang, “We can discover the wonders of nature / Rolling in the rushes down by the riverside.”

The first Earth Day had occurred just a year earlier. “I helped arrange some of the speakers and the teach-ins at my own campus,” said Ron Beard, one of the four crew leaders in the AYCC, who later became a community development expert at University of Maine Cooperative Extension. “We really felt both a responsibility and an opportunity to teach high school students about the environment and to work collaboratively with the environment.”

AYCC staff and participants in 1973 included the highly regarded

cook, Gene Foster, here in his white chef hat. (Photo courtesy Bob Chaplin)

Fellow crew leader Cathy Johnson, who in 2020 received the Natural Resources Council of Maine’s Conservation Leadership Award for Lifetime Achievement, called the program a “wonderful opportunity” to get work experience, learn about the environment, work as a team, meet people (who, for many, became part of a life-long network), and have fun.

She recalled that recruits were primarily from Bangor and Portland, “kids who had not generally been in the outdoors and not done a lot of physical labor.” The 1970 law itself specified the program would promote “gainful employment during the summer months of American youth, representing all segments of society, in the healthful outdoor atmosphere” of national parks and other public lands.

Assignments – like clearing leaf litter and maintaining Acadia’s historical sites – were coordinated through Martin Beavers, the program’s first director. Support was strong from both park superintendent Keith Miller and chief ranger Tom Hobbs, who “was really fired up about doing this,” said Chaplin. The first year enrolled 34 teenagers, ages 14-18, with an equal number of girls and boys.

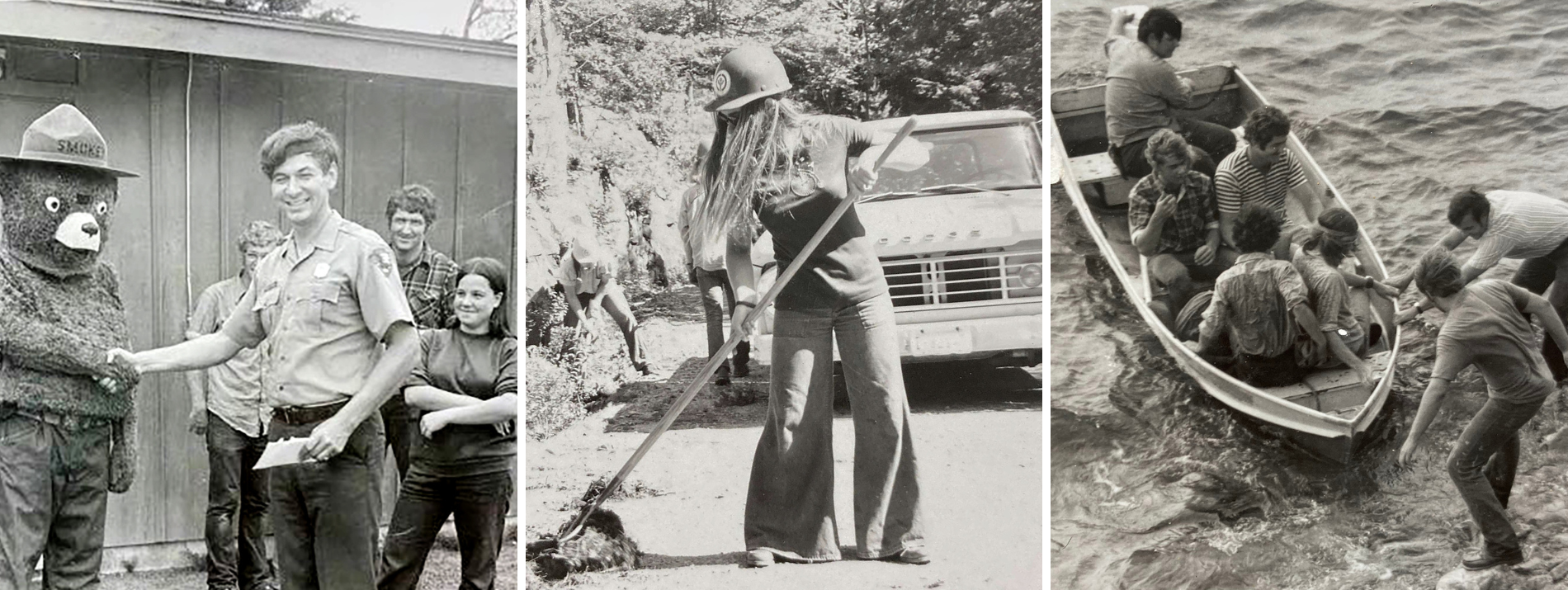

Education head Bob Chaplin, here shaking hands with Smokey,

was sometimes called Uncle Bob. Hardhat and bell-bottoms were a common

uniform of the AYCC in the 1970s. Landing a boat a Bald Porcupine Island. (Photos courtesy Bob Chaplin)

The new Youth Conservation Corps channeled the public works commitment of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a program that put over three million men to work during the Great Depression. But in 1970 the mandate was to hire both young women and men. Female and male crew leaders assigned work equally to co-ed work crews. “That was by design, not accident,” added Chaplin.

“We had a number of girls who arrived thinking that they couldn’t do a lot of things and left feeling very empowered,” said Johnson. They learned they could use chainsaws, drive buses, and remove boulders. Some even had the opportunity to climb Mount Katahdin in Baxter State Park, a special trip during some of the early years.

Unlike today’s program, the early AYCC was residential, with housing at the national park headquarters. There were strict rules: no alcohol and no leaving the premises without permission. One young woman, who broke both rules, was sent home. (Her father was in the Maine legislature, Chaplin remembered). There were no further infractions.

The crew leaders, who were in their early 20s, and the high school participants were given “a lot of responsibility,” said Johnson. It took many out of their comfort zones. But they had support as well.

From the CCC, they inherited shovels, rakes, pry bars, buses and trucks – ancient stuff, but it functioned thanks to the skill of Acadia’s maintenance chief Ted Staples. “He really loved the kids,” said Chaplin.

Restoration of the Gilley House

on Baker Island, which included repainting, was a major AYCC project. (Photo courtesy Bob Chaplin)

The early AYCC crews restored Shore Path and other trails. They cut cedar trees in swamps to build log steps. They shingled the 1852 Blue Duck ship hardware store in Islesford.

Each project offered an opportunity for education, a serious commitment of the program. Before cleaning leaf litter from carriage road culverts, for example, the crew learned about erosion and the contributions of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

“If they could learn about it before they did the physical labor, the more enthusiastic they were and the better the project became,” said Chaplin.

Another time, the AYCC restored the historic house on Baker Island where William Gilley became the first keeper of the 1828 light station. (Acadia still preserves the homestead as tangible history of nineteenth century farming and maritime life in Maine.)

To start, the AYCC set up a camp site for itself. Crews alternated weekly, working to remove the roof down to its cedar rafters and then rebuilding it up to laying new shingles. Back in Bar Harbor, they interviewed Leona Gilley, the great granddaughter of William and Hannah and the last baby born on the island in 1890. Despite her age, she agreed to join the AYCC to see their work.

As they left Northeast Harbor, a parade of lobster boats from Little Cranberry Island suddenly appeared and, with horns blowing, led the way to Bakers Island.

“We showed her all around and she was so excited about being on the island where she grew up,” said Chaplin, who could not suppress tears as he told the story. “We tried to do very meaningful projects.”

1995 AYCC group photo. Jesse Wheeler, vegetation program manager at Acadia, is at center in the green jacket and no hat. He’s behind Pete Colman and to the left of Chris Bater, both of whom work in the park today as part of the trails crew. (Courtesy photo)

Since the program was a pilot, it didn’t come with a manual. There was an opportunity to design and create something that fit Acadia, Chaplin emphasized.

Beard recalled an environmental education session at Sand Beach led by Chaplin when the teenagers learned how sand dunes protect against storms and dune vegetation prevents erosion. One young man took the lesson to heart and asked the maintenance staff to help him create a sign to protect the dunes. “For years, I would routinely take people to Sand Beach and point out that sign as a YCC project.” The teen who took that initiative, Greg Rainoff, would later create visual effects on the popular Star Trek franchise.

As a project leader, Cathy Johnson also thought independently. One crew assignment was to clear a scenic vista from a roadway. “I was conflicted about cutting down trees because people could get out of their cars and walk 20 or 30 feet,” she said. The park, on the other hand, was thinking about access for people who couldn’t walk and slowing down traffic through the distraction of a vista.

“I struggled with those competing goals, and that was really the beginning of my thinking about policies and how policies work. All of that eventually led to going to law school and working at NRCM,” the Natural Resources Council of Maine. There, despite strong political and community opposition, she was key to the creation of Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, which spans over 85,000 acres of mountains and forestland donated by Burt’s Bees founder Roxanne Quimby.

(By the way, Johnson and her crew were given an alternative assignment and not forced to cut down trees.)

Group photo of the AYCC in 1999. (Courtesy photo)

Ron Beard, who went on to earn a master’s in agricultural resource economics and viewed his community development career “as a strategy for making change,” said of the AYCC’s early years, “We worked hard, played hard, and ate very well,” courtesy of Gene Foster, an ex-Navy cook who prepared their meals. “He is the only guy I know who could get teenagers to eat liver,” Chaplin added.

The group would go swimming at the end of the day. One of Chaplin’s friends gave him a popcorn machine which they’d use on movie nights. On weekends, they’d go white water tubing.

One field trip was to Machias to see the site of the first naval battle of the American Revolution, sometimes called “the Lexington of the seas.” They visited a historic tavern-turned-museum. “We brought our sleeping bags and slept in the Jeremiah O’Brien Cemetery,” the burial ground of the hero of the battle, Chaplin said.

For many years later, Chaplin’s impact would continue in the Bar Harbor school system, where he became a beloved science teacher whose innovations included the first outdoor learning labs. His talents were recognized nationally with a Presidential Award for Excellence in Science Teaching.

2022 AYCC rehabilitates and replaces a section of the bog walk along the Duck Harbor Trail on Isle au Haut. (Photo by Sam Mallon/Friends of Acadia)

Federal support for the AYCC continues, despite a hiatus in the 1980s. For two decades, its work in Acadia focused on trails. But after COVID shuttered activities during 2020 and 2021, leaders broadened its scope to include multiple areas.

Through an anonymous gift in 1999, Friends of Acadia now helps fund the program, which welcomed 13 participants in 2023.

“Almost any local islander I talk to knows someone who did AYCC growing up. The influence is widespread. Several of our current [National Park Service] employees were participants,” said Erica Lobel, AYCC coordinator.

As if on cue, Jesse Wheeler walked through the doors of the McFarland Hill headquarters. Today’s Acadia vegetation ecologist and specialist in invasive species, he was a member of the AYCC in the 1990s. Asked if it changed his life, he replied, “It’s why I’m here now.”

LYNN FANTOM is a former New York advertising executive who has embraced her second career as a freelance writer in Maine.