A Passion to Serve

Then: Margaret Stupka, a trained botanist, was among the many “park wives” in the 1920-1940s. Now: Zoë Smiarowski is a recent National Park Service intern on women’s history.

August 2nd, 2022

Then: Margaret Stupka, a trained botanist, was among the many “park wives” in the 1920-1940s. Now: Zoë Smiarowski is a recent National Park Service intern on women’s history.

August 2nd, 2022

Zoë Smiarowski (right) and Miriam Nelson work to finish up widening the Hadlock Ponds Trail that a service group worked on earlier that week in Acadia National Park. (Photo by Ashley L. Conti/Friends of Acadia)

By LYNN FANTOM

This is the final feature in the Women of Acadia: Then & Now series recognizing women of Acadia, both past and present. View the full series.

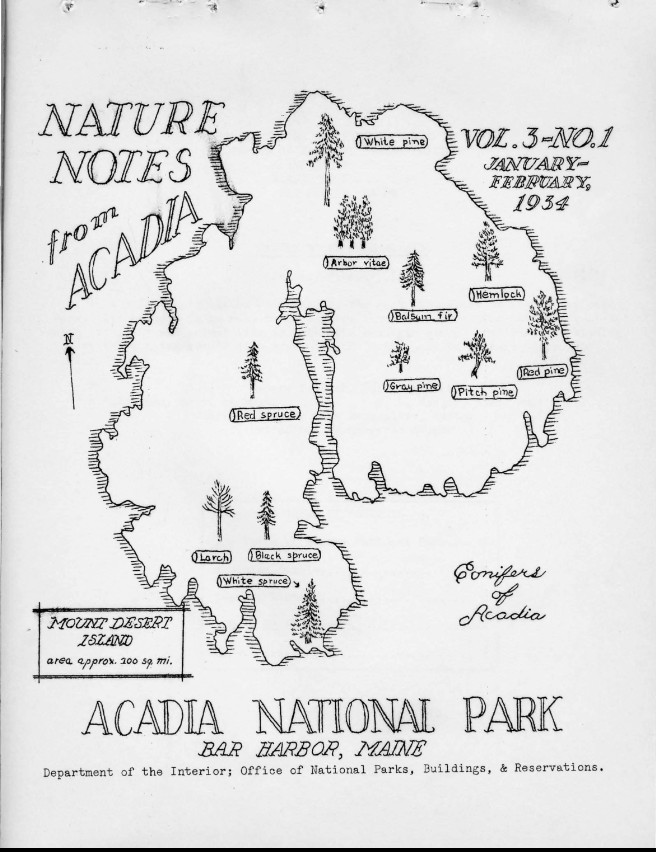

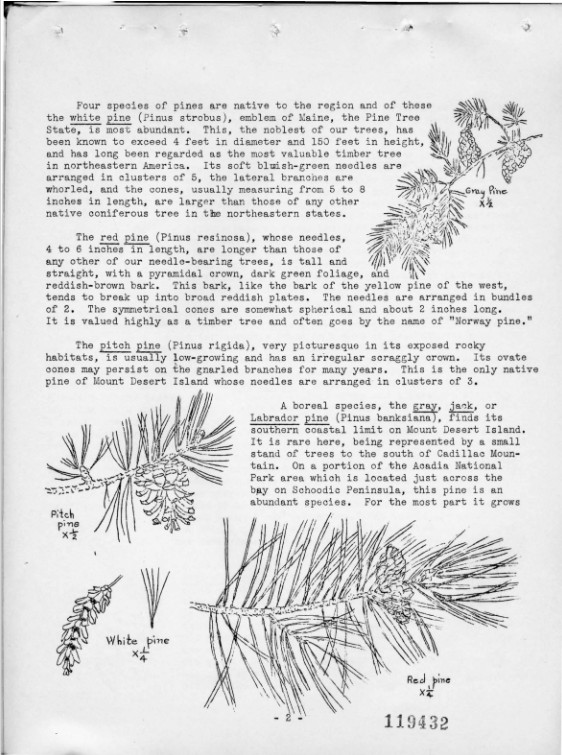

Margaret Stupka, a trained botanist, was among the many “park wives” in the 1920-1940s who served the National Park Service without pay. When Margaret’s husband, Arthur, was hired as the park’s first ranger-naturalist in 1932, Acadia “bought one and got one free.” Their first summer, the couple organized four wildflower exhibits and created the bimonthly bulletin Nature Notes, for which Margaret wrote and illustrated features. Although Margaret wasn’t paid, she was recognized both in the Nature Notes masthead and in an annual report where her husband noted, “For two summers Mrs. Stupka has donated her entire time aiding the cause of the Ranger-Naturalist Service in a very capable and enthusiastic manner.”

Zoë Smiarowski is a recent National Park Service intern on women’s history.

The cover of Nature Notes from Acadia from January/February 1934. Margaret Stupka contributed greatly to the publication with insights and drawings, although she was never paid for her work.

“Even though I am paid, and she was not,” Zoë Smiarowski, a recent National Park Service intern on women’s history, feels aligned with Margaret Stupka because of their mutual passion and desire to share knowledge about natural resources.

At 25, Zoë has already invested her energy into land stewardship and outdoor education, working with the National Park Service (NPS), state parks, and organizations like Friends of Acadia. Recently, she turned to women’s contributions to Acadia National Park.

During a four-month internship funded by the National Park Foundation, Zoë unearthed women’s stories and brought them to light not only for NPS personnel but for the public. She dug into resources from Pennsylvania’s Bryn Mawr College (the alma mater of Florence Bascom, a professional geologist who surveyed Mount Desert Island and published her work in 1919) to the Denver Public Library (for files about the Student Conservation Association, which has placed both women and men into positions at Acadia since the 1960s).

But Zoë didn’t hole herself up with historical archives in her office, though its walls did display some beautifully illustrated Margaret Stupka articles. She also reached out to community experts, such as Terese Miller, a Mount Desert Island teacher and Bar Harbor Historical Society lecturer, and enthusiastically credits a range of collaborators.

That kind of generosity is part of Zoë’s charm, along with a big dose of humility about the resulting work, some of which is showcased on the Acadia National Park website. It is both comprehensive and insightful.

“One of my biggest takeaways was that women were really a large part of getting the park established,” she says. She points not only to the wealthy women, like Eliza Homans (1832-1914), who funded trails and made land donations, but also to conservation advocates such as Belle Smallidge Knowles (1871- 1959), active even before women had the right to vote. “Both helped create a reputation that this is a place that deserves protection,” she adds.

Another of Zoë’s insights: women did not dominate just one corner of the story. In science, for example, Annie Sawyer Downs (1836-1901) was a botany expert credited with discovering the white variety of Rhodora. (She also founded the Southwest Harbor Public Library.) Barbara Patterson (1912-1991) was a citizen scientist who recorded over 23 years of bird banding data on Mount Desert Island, now a resource at NPS to help scientists assess changes in bird behavior and activity.

Zoë herself is a generalist. “When you look at my resume, I’ve dabbled in all different kinds of land stewardship,” she says. A 2019 University of Connecticut graduate, the Branford native majored in Natural Resources and the Environment.

With a connection to Mount Desert Island from summertime visits with her grandparents, she later worked as a Friends of Acadia Summit Steward for two and a half years. She then joined AmeriCorps and served as a trails specialist in Montana, organizing volunteers and developing resources, such as a trails management plan. Upbeat about what she learned from that experience, she does admit that on the prairie, “I definitely missed trees.”

Now back in Maine, with the NPS internship on women’s history concluded, she has started a new position at Friends of Acadia helping organize volunteer groups who come to work on trails, carriage roads, or other vegetation projects. She quickly notes that it was a woman, Marianne Edwards, who had the idea to bring more structure to volunteering at Acadia and became the driving force behind the founding Friends of Acadia in 1985, as well as its first donor.

“It feels nice to be part of that legacy,” she says.

A page from Nature Notes of Acadia, in which Margaret Stupka wrote about the distinction between the region’s pine trees. See more Nature Notes on the NPS website.

LYNN FANTOM is a former New York advertising executive who has embraced her second career as a freelance writer in Maine.