Big Nights:

Helping Amphibians Cross the Road

Acadia Science Fellow Marisa Monroe and a team of volunteers collect data on crossing amphibians and prevent their undue mortality along the way.

April 2nd, 2025

Acadia Science Fellow Marisa Monroe and a team of volunteers collect data on crossing amphibians and prevent their undue mortality along the way.

April 2nd, 2025

BY TREVOR GRANDIN

On a drizzly, early May night, Sieur de Monts Road was littered with catkins, leaves, and small branches.

“Here’s one… or maybe it’s a twig,” I called out. Acadia Science Fellow Marisa Monroe chuckled. She knew the roller coaster of emotions one goes through when mistaking a twig for a salamander. Throughout the evening, we observed plenty of amphibians—pickerel frogs and wood frogs, spring peepers, red-backed and two-lined salamanders, and red efts – all seen in the span of one rainy night. The dozens of amphibians that Monroe and I saw on that survey don’t begin to scratch the surface of what “big nights” are all about.

Amphibians – translating to “double life” – are often aquatic during their larval and juvenile phases, transitioning onto land for their adult lives. In the winter, amphibians store themselves under leaf litter, in underground burrows, or at the bottom of deep water bodies to ride out the bitter cold months. When the nights become milder and the rains more abundant, frogs, toads, and salamanders emerge from their hibernation to hatch a get-warmquick scheme. For some, that involves splaying on a nearby road to take advantage of the ambient heat absorbed during the day.

As spring wears on, the urge to cross roads is spurred by a more reproductive instinct.

Amphibians spend much of their lives traversing the forest but return to vernal pools, lakes, or ponds to breed and lay eggs. This prenatal pilgrimage takes place in early spring during warm, wet nights to ensure the sensitive-skinned amphibians stay damp. Once in the water, the animals find a mate, then deposit their unhatched young. After the froggy bacchanal, the adult amphibians return to their forests to start the freeze and thaw process over again. That’s what the term “big night” refers to the biggest nights when amphibians emerge from winter hibernation

and take to the streets for warming and reproduction.

This natural cycle would go on uninterrupted if not for one big problem – cars.

A frog is captured in headlamp light while crossing the road during a damp spring night. (Courtesy Trevor Grandin)

Amanda Mogridge holds a spotted salamander in her hands as she carries it across Eagle Lake Road on Mount Desert Island in May 2024. (Photo by Shannon Bryan/Friends of Acadia)

Roads often intercept amphibians’ spring journeys to and from the water, forcing these slimy critters into the paths of motorized vehicles. Though frogs, salamanders, toads, and newts lay many eggs, car strikes still put them at risk of extirpation – or localized extinction.

Enter Acadia Science Fellow Marisa Monroe.

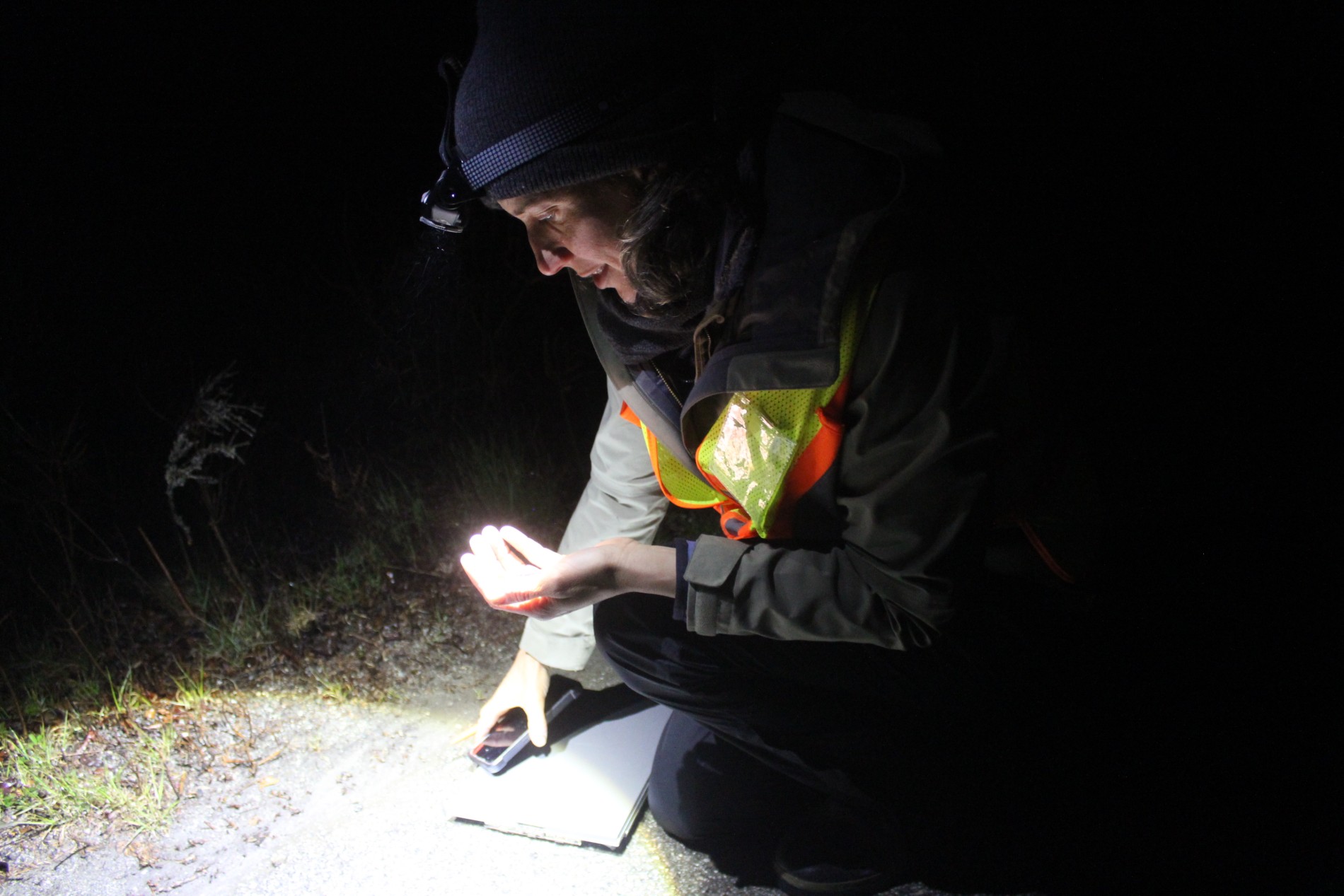

On rainy nights, clad in headlamps and reflective vests, Monroe and volunteers collect data on crossing amphibians and prevent their undue mortality along the way. From spring to fall, participants walk their stretch of adopted roadway and note amphibians both alive and dead while giving those actively crossing help to the other side.

Despite “big nights” primarily taking place during the spring, Monroe and volunteers continue their surveys into the fall to account for the most vulnerable – the babies.

While adult amphibians return to the forest, juveniles grow in their ponds and pools until they too must sprout legs and cross roads. Other amphibian assistance organizations stop patrolling in late spring, before the babies hatch, but Monroe’s survey bridges that gap to learn more about migration during the rest of the year.

“Even if we save all of the adults that are migrating in the spring to their breeding habitats,” Monroe said, “if we ignore all the juveniles when they leave the pool, and they all get hit by cars, then their population could still be at risk for decline or extirpation.”

Clad in a safety vest and headlamp, Marisa Monroe carries an amphibian found on the road to the grassy shoulder. (Courtesy Trevor Grandin)

The data on where and when amphibians cross could lead to more long-term solutions within Acadia National Park, like permanent migration culverts or seasonal road closures. “The park is interested in saving their amphibians,” Monroe said. “And it’s exciting that there’s a lot of motivation behind this project.”

As we finished our Sieur de Monts survey that May night, I realized I would now need to drive home on the same road Monroe and I had just surveyed. “I’ll clear your path,” Monroe said, stepping in front of my idling car and turning her headlamp on. She carefully scooped up frogs frogs, salamanders, toads, and newts, ferrying them to the grassy shoulder. As my car inched along behind her, I realized just how precious these creatures are and how slowly I’d be driving home that night.

Hear more about “big nights” and Trevor’s time with Acadia Science Fellow Marisa Monroe on season 3, episode 3 of Acadia National Park and Schoodic Institute’s podcast “Sea to Trees.” Listen on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever podcasts are available.

TREVOR GRANDIN was a 2024 Cathy and Jim Gero Acadia Early-Career Fellow at Schoodic Institute.

There might be organized Big Night opportunities in your area, where you can volunteer and collect data as a community scientist (not to mention the chance to escort amphibians across the road).

In Maine, check out Maine Big Night, a community science initiative that saves thousands of amphibians each year and collects data to inform wildlife conservation and improve road planning. Go to mainebignight.org to learn more about getting involved.

Amphibians have porous skin and are sensitive to the products or food that might be on your hands, so be sure to wash your hands thoroughly before handling an amphibian (and after)! And do stay safe on roads at night by wearing a high visibility vest and a headlamp, in addition to being mindful of moving traffic.

Frogs are easy to ID—as frogs, at least. And while all toads are frogs, not all frogs are toads. Can you identify these handsome hoppers?

Take the Quiz!