Wild Gardens of Acadia Visitor Information

Displaying, preserving, and propagating Acadia’s native flora. Located at the Sieur de Monts area of Acadia National Park.

Displaying, preserving, and propagating Acadia’s native flora. Located at the Sieur de Monts area of Acadia National Park.

Created in 1961 and maintained by dedicated volunteers, the Wild Gardens of Acadia offers park visitors an award-winning microcosm of Acadia’s uniquely varied plant communities in a serene brookside setting.

The Wild Gardens includes over 400 plant species, all indigenous, in thirteen sections designed to represent natural plant communities found within Acadia National Park. Mountain, heath, seaside, coniferous forest, and nine other habitats are represented.

The gardens are open daily from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. during the summer. After Labor Day, the gardens are open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

View a pdf of our Wild Gardens of Acadia brochure. There will be a scannable QR code at the garden gate to access it with a smart phone or mobile device.

Mount Desert Island is unique for its beauty and glacial accidents which left it with flora from both the cold north and the warmer south. In the early 1900s, Charles W. Eliot and George B. Dorr recognized these special qualities and began to acquire land to be preserved for public enjoyment and for “educational and scientific purposes.” Dorr bought the Sieur de Monts Spring area in 1909, named it the Wild Gardens of Acadia, and eventually presented it to the United States government as part of what is now Acadia National Park.

In 1961, Acadia’s superintendent, Harold Hubler, offered a three-quarter acre plot to grow and display wildflowers grown by participants in a propagation program sponsored by the Bar Harbor Garden Club. Although the plot was covered with blackberry bushes and mature red maples damaged by the 1947 fire, its assets included a wealth of large ferns and a winding brook fed by Sieur de Monts Spring. The Wild Gardens of Acadia committee, comprised of members of area garden clubs and other interested gardeners, began laying out paths and divided the Gardens into areas simulating natural plant communities. The decision to include only those species indigenous to Acadia precluded planting daisy, yarrow, lupine, rugosa rose, purple loosestrife, and clover, all of which are abundant on Mount Desert Island but not native.

Guided by Edgar T. Wherry’s Wild Flowers of Mt. Desert Island, published in 1928 under the aegis of the Garden Club of Mount Desert, volunteers established more than 400 indigenous plant species. These efforts have been recognized by awards from the Garden Club of America, the New England Wild Flower Society, the Garden Club Federation of Maine, the National Council of State Garden Clubs, and the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. The National Park Service presented a Certificate of Appreciation to the Wild Gardens of Acadia committee in 1979 and a Partnership Award in 2011 in recognition of the “Wild Gardens of Acadia Volunteers for 50 years of devoted stewardship.”

In 2010, the Wild Gardens of Acadia became an official committee of Friends of Acadia and formalized this new standing through a partnership with Friends of Acadia and Acadia National Park, a partnership that ensures the Gardens’ viability and provides additional support and guidance. The Gardens not only enhance understanding of native plants and their habitats but also foster stewardship—ensuring that parks and gardens continue to be preserved through volunteers and private philanthropy. The Gardens are maintained primarily by volunteers, along with a supervisory gardener and summer intern funded by Friends of Acadia, while docents greet and orient visitors. The gardeners and committee plant, study, collect, propagate, label, and fund-raise, with administrative support from Friends of Acadia. Beyond this, the budget is met by grants, gifts from individuals, the Garden Club of Mount Desert, the Bar Harbor Garden Club, plant sales, and the sale of cards and leaflets at the Gardens entrances. In its early years, the Wild Gardens committee was comprised of interested individuals, some of whom belonged to the Bar Harbor Garden Club, the Bass Harbor Garden Club, and the Garden Club of Mount Desert. Recently the Gardens have received support from the Hancock County Master Gardeners.

If you enjoy your visit to the Wild Gardens of Acadia, please consider making a contribution to Friends of Acadia toward the maintenance of the Gardens.

The Wild Gardens of Acadia is located at the Sieur de Monts area of Acadia National Park. The entrance is on Route 3 approximately 2 miles south of Bar Harbor’s Village Green.

The best season to visit the Gardens is May through October, when habitat signs and plant labels are in place. The rest of the year, there may be snow in the gardens and the gates may be locked. Please follow the rules posted at the main entrance to the Gardens, including 1) no eating or picnicking, 2) no dogs, and 3) no picking of flowers or plant materials.

Many factors affect the habitat of a plant: sunlight and wind, temperature and elevation, the availability and nature of the water, the topography or lay-of-the-land, the type of bedrock and soil, and a history of fire or other disturbance. Plants are also affected by the other plants growing in the same location, as well as by the habitat’s animals and especially the microorganisms in the soil. The plant community reflects all of these factors to such an extent that the plants growing in one place tell us a lot about that environment.

Gardeners try to create a good, “rich” soil, which is high in the elemental nutrients that garden plants need. The soil must also have a texture that is porous enough for air, water, and nutrients to move through it. Unlike garden plants, wild plants are not so lucky and have adapted to a variety of soil and environmental conditions.

Gardeners try to create a good, “rich” soil, which is high in the elemental nutrients that garden plants need. The soil must also have a texture that is porous enough for air, water, and nutrients to move through it. Unlike garden plants, wild plants are not so lucky and have adapted to a variety of soil and environmental conditions.

Acadia National Park is at the southern limit of growth for a number of plants, such as the arctic blue flag iris, that normally occur much farther north. Yet Acadia is also home to plants like pitch pine and bear oak that typically grow in the mid-Atlantic region. The result is that Acadia National Park, for such a small part of Maine, has an extraordinary variety of plant species. In order to demonstrate this diverse flora, the Wild Gardens of Acadia have tried to mimic the growing conditions found in the diverse habitats of Acadia National Park.

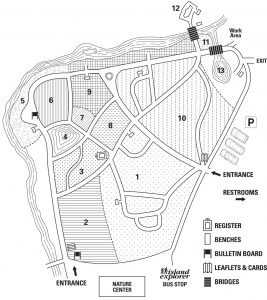

In order to share with you this diverse flora, the Wild Gardens of Acadia have tried to mimic the growing conditions found in these ecosystems of the park. Numbers refer to sections on the map below.

1. The MIXED WOODS present a transitional forest between one that is composed not only of deciduous hardwoods, which prefer richer soil and a warmer climate, but also the northern coniferous forest whose evergreen trees tolerate more acidic, cooler soil with fewer nutrients. These woods grow on loose glacial till where the terrain is gentle. Here a deep fertile soil has accumulated and is capable of supporting large trees. Indeed, trees define this forest: look for white pine, eastern hemlock, northern red oak, American beech, sugar maple, red maple, and yellow birch. The sunlight-dappled understory has interesting wildflowers, but many are ephemeral and disappear by early summer. A bulletin board in the Wild Gardens lists plants currently in flower (during the growing season).

Ferns are sensitive to soil moisture and the presence of certain nutrients, so you might not find all of these fern species growing side-by-side in the wild, but here the Fern Path creates a lush and informative diversion.

Within the Mixed Woods, there is a small stand of northern white cedar. These lowland forest swamps are home to many unusual northern birds; as you explore the park, look for them: palm warbler, yellow-bellied flycatcher, and northern waterthrush.

2. Some plants prefer sunny disturbed areas and these you find in abundance along the ROADSIDE. Here several kinds of brambles and goldenrods grow in front of an old stone wall, alongside hawthorn, shadbush, and viburnum. Unfortunately, the disturbed shoulders that line roadways may offer invasive, non-native plants a chance to become established. But you won’t see these exotics in the Wild Gardens, since we grow only native plants.

3. MEADOWS are impermanent communities here. In coastal Maine, only disturbance—fire, flooding from beavers, the scouring action of river water and ice, or human intervention—keeps meadows from becoming woodlands. Many small plants—strawberries, violets, and pussytoes—love the sunny, sometimes damp meadow as do the larger and later-blooming dogbane, fireweed, groundsel, roses, and meadowsweet. The Meadow is most regal in late summer when goldenrods and purple asters bloom. We mow this Meadow yearly to prevent the return of the forest.

4. On the steep exposed bedrock of a MOUNTAIN, wind, rain, and gravity prevent soil from accumulating, and the hard granite of Acadia doesn’t decompose readily. The thin soil and harsh conditions of these bald summits limit the flora to tiny plants, low shrubs, and stunted trees. On our Mountain, you may spot the tiny spleenwort fern and the progressively larger crowberry, three-toothed cinquefoil, bearberry, columbine, blueberry, juniper, and bear oak.

5. The BEACHES of Acadia National Park vary: no two are quite alike. They range from granite-and-shell sand to large cobbles tumbled by crashing waves. However, the plants growing on the upper reaches of any beach are deeply rooted and all are subject to salt, wind, and occasional inundation. This area, constructed and maintained by the introduction of seaweed and beach gravel, supports several uncommon coastal headland plants: roseroot sedum and arctic blue flag iris. Plants you are likely to find on sea beaches and in this habitat are beach-peas, lovage, skullcap, silverweed, and large beach grasses.

6. A HEATH has poor, often sandy, acidic soil—conditions preferred by members of the “heath” family, Ericaceae. Blueberry, huckleberry, rhodora, and lambkill belong to this group.

7. The PITCH PINE UPLAND is dry and open. Look for pitch pines on south- or west-facing slopes, in old quarries on Mount Desert Island, and along the Tarn. They are Acadia’s only pine with needles in bundles of three. Where drainage is good, shrubs such as huckleberry, shadbush, bush-honeysuckle, sweet-fern, and chokeberry may grow. Fire maintains this type of woodland, and pitch pines are adapted to it. They can re-sprout after a fire and, as a result, sometimes assume a natural bonsai shape.

8. The BIRD THICKET features native plants that provide wildlife with a variety of foods such as buds, nectar, fruits, seeds, and accompanying insects. To attract birds, choose plants so that the feast spans the entire season. A diversity of plants (both living and dead) provides a structural mix of shapes and heights that can be used for cover or nest sites by birds with differing needs. Space between groups of plants helps those animals that thrive on edges. Finally, whenever the goal is to attract wildlife, don’t forget to provide water.

9. The certainty of water makes the BROOKSIDE, stream shores, and other riparian habitats competitive environments for plants. Vines and trees reach for the sun, but after these overhead plants leaf out, they shade the lower non-woody plants which must be adapted to summer shade and moist ground. If you look across the stream, you may spot trees that have been gnawed by beavers, which are especially fond of birch and aspen.

10. The coastal CONIFEROUS WOODS of Acadia National Park say “Maine.” Lichen-clad red spruce, white spruce, and balsam fir cling to coastal rocks that are only thinly covered with soil. Often these trees are pruned by the wind. Away from the fog and salt spray, these conifers are joined by larger cone-bearing trees such as white pine, red pine, and eastern hemlock, as well as some hardwood trees, to become part of the vast northern spruce-fir forest.

11. MARSHES are shallow wetlands with emergent vegetation, non-woody plants growing up out of the water. These plants have roots adapted to growing in submerged soil. Our marsh has a stream flowing slowly through it, bringing in sediment and making a rich muck favored by many typical marsh plants: sedges, buckbean, St. John’s-wort, blue flag, and bristly rose.

12. BOGS form in basins with poor drainage. Often Acadia’s bogs are lined with clay that was deposited during the last ice age. Unlike a marsh or a swamp, bogs have little water flowing through them—they are mostly fed by rain. The partial decomposition of plants makes the water acidic; the acidity and lack of oxygen make it a hostile environment for bacteria. Without bacterial decomposers, plant debris builds up, forming peat. A surprising collection of dwarf evergreen shrubs, many small orchids, and carnivorous plants—like the pitcher plant—have adapted to this still, cool, peaty wetland.

13. The open water of the POND is thick with floating vegetation. These plants are anchored on the bottom, but have leaves and flowers at the surface. Some parts of these plants provide flotation, allowing the plant to use space that others cannot. Notice how the vegetation forms rings around the pond edges, depending on the species’ tolerance for a watery footing. Water-lily and pickerelweed are surrounded by horsetail and cat-tail, and on the banks grow sweetgale, steeple-bush, and turtlehead. Our pond has few fish because it is fed by water from the Sieur de Monts Spring; this is just fine with the many tadpoles growing up here.

The Plants of Acadia National Park by Glen Mittelhauser, Linda Gregory, Sally Rooney, and Jill Weber (2010).

The Wild Gardens of Acadia by Anne Kozak and Susan Leiter (2016).

Other Plant Guides

A Field Guide to the Ferns and their Related Families by Boughton Cobb, Elizabeth Farnsworth, and Cheryl Lowe. Second edition (2005).

Flora Novae Angliae: A Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England by Arthur Haines (2011).

Forest Trees of Maine by the Maine Forest Service (2008). Fact sheets available at: www.maine.gov/doc/mfs/pubs/ftm/ftm_centennial.html

Go Botany. New England Wildflower Society’s website: gobotany.newenglandwild.org

Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide by Lawrence Newcomb and Gordon Morrison (1989).

On Plant Communities

Natural Landscapes of Maine: A Guide to Natural Communities and Ecosystems by Susan Gawler and Andrew Cutko (2010). Fact sheets available at: www.maine.gov/doc/nrimc/mnap/features/commsheets.htm

On Cultivation

Three books on growing North American native plants: Wildflowers (2000); Native Trees, Shrubs, and Vines (2002); and Native Ferns, Moss, and Grasses (2008), all by William Cullina.

On Birds

National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America by Jon L. Dunn and Jonathan Alderfer. Fifth edition (2006).

The Sibley Guide to Birds by David Allen Sibley (2000).