Wild Gardens of Acadia: The Bog

Bogs are unique and challenging ecosystems. To thrive in adverse conditions, bog plants employ surprising strategies – including carnivory and cloning.

BY HELEN KOCH

Bogs are unique and challenging ecosystems. To thrive in adverse conditions, bog plants employ surprising strategies – including carnivory and cloning.

BY HELEN KOCH

A typical central Maine raised bog. (Photo by Helen Koch/Wild Gardens of Acadia)

Like marshes and swamps, bogs are a type of wetland, but unlike those habitats, little flowing water passes through a bog. Northern bogs generally occur in poorly drained depressions left by the last glaciers. Instead of flowing water, the water in a bog comes primarily from rain and snow – precipitation that lacks the benefit of mineral nutrients brought in by flowing streams. Low oxygen levels in this still and saturated environment limit bacteria, and thus decomposition is slowed.

Normally, decomposition not only recycles vital elements such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium but also makes them available for other plants. In bogs this does not happen. In addition, the weak acids from partially decomposed plants, the lack of minerals that would buffer the acids, and the remarkable ability of peat moss (Sphagnum) to further acidify the environment all combine to make the bog a very acidic place.

The low nutrients, little oxygen, and high acidity make the bog a challenging habitat for plants – but with challenges, come opportunities for invention. To thrive in adverse conditions, bog plants have evolved a number of surprising strategies including nutrient conservation, carnivory, and cloning.

To compensate for the low level of available nutrients, bog plants have adapted other ways to sustain themselves. Some, such as the bog-rosemary, have thick evergreen leaves that can last several years, and this conserves the plant’s resources. Other bog plants (pitcher plants and sundews) are carnivorous and use specialized leaves to trap and devour invertebrates for protein. Bog plants can also save energy by reproducing vegetatively rather than relying on seeds. Seed production is energetically expensive, and so some bog plants, such as the leatherleaf, make new plants via their spreading roots.

Peat Moss (Sphagnum, many species) dominates the bog ecosystem and is a habitat manipulator. This little moss exchanges the scant minerals it takes up for acids, further acidifying the bog. Sphagnum peat moss forms a creeping carpet that can drown other plants due to its ability to hold many times its weight in water. New moss grows on top of the old, eventually elevating the bog’s surface since the old, underlying moss doesn’t break down. Whenever plants grow faster than dead plant matter disintegrates, “peat” is formed.

Sphagnum has distinctive “pom-pom” heads, and outside of bogs, you can find other species of peat moss in damp spots in our forests.

Three species of Sphagnum peat moss. (Photos by Helen Koch/Wild Gardens of Acadia)

Pitcher Plants (Sarracenia purpurea) are 6-12” carnivorous plants with modified leaves that form water-holding cups. Attracted by the colorful, nectar-scented cups, insects enter the tubular leaves but the downward-pointing hairs make it difficult for them to climb back out. The insects drown and are digested by the community of microbes that live in the water-filled pitcher. The remains of the insects are absorbed by the plant. Along with the microbes, the pitcher plant’s cup supports a mini ecosystem: insects and spiders use the pitcher for shelter, as a nursery for their eggs and larvae, and as an opportunity to eat the drowning insects.

Purple pitcherplant (Sarracenia purpurea) nestled into peat moss. (Photo by Dave Easler)

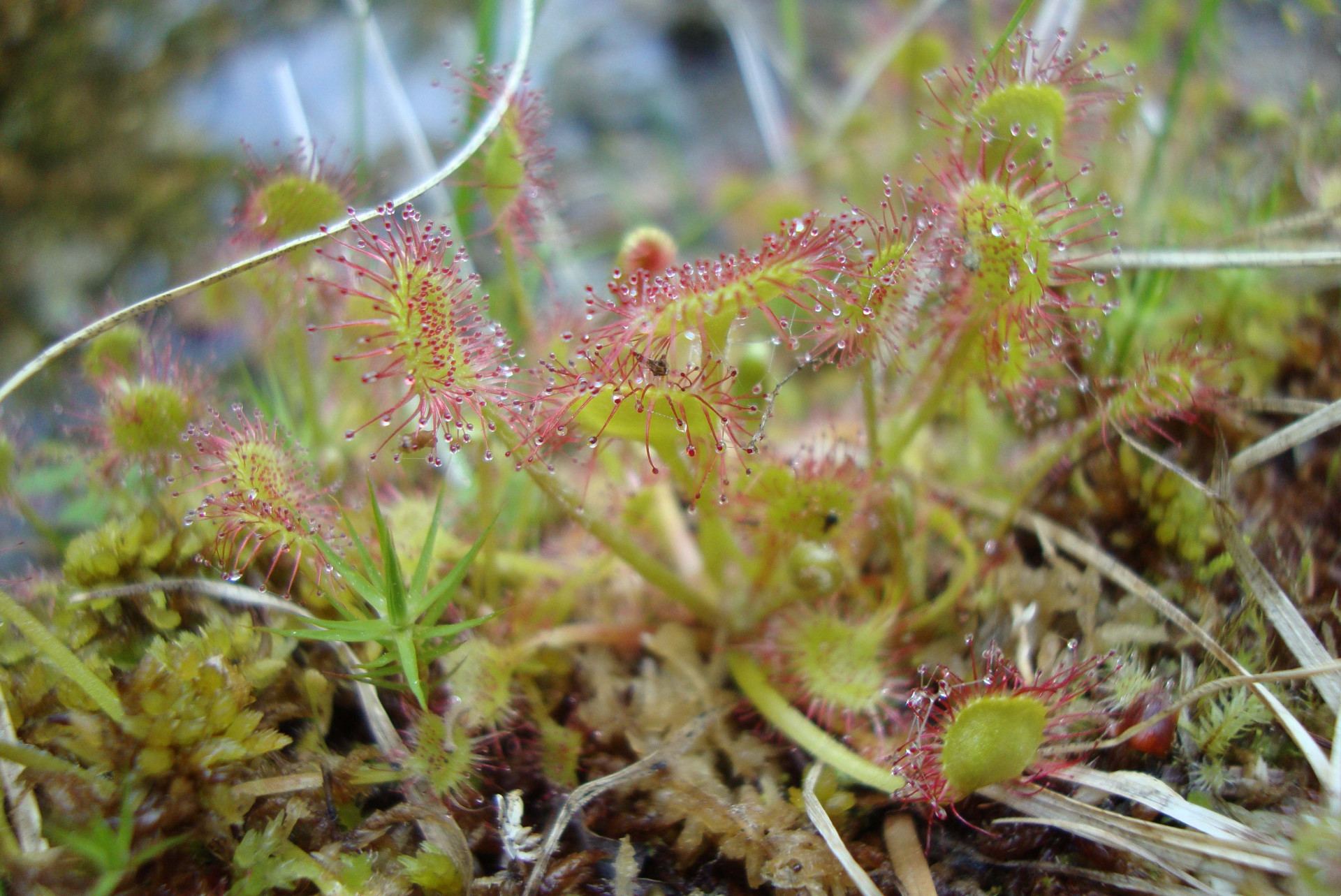

Round-leaved Sundews (Drosera rotundifolia) are tiny carnivorous plants with a rosette form topped by specialized round leaves. These leaves have sparkling, glue-like liquid drops around their edges. Insects mistake the drops for nectar and become stuck. When this happens, the leaf wraps around and digests the insect.

Round-leaved sundew (Drosera rotundifolia). (Photo by Alison C. Dibble)

Leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), Bog-rosemary (Andromeda polifolia), and Labrador-tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum) are all compact evergreen shrubs native to bogs. Members of the Heath family, their leaves are tough, waxy, or hairy: these attributes help the plant conserve water and energy because the leaves last for several years; that way, they don’t have to be re-grown each spring.

Leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata). (Photo by Charlotte Stetson/Wild Gardens of Acadia)

Bog-rosemary (Andromeda polifolia). (Photo by Charlotte Stetson/Wild Gardens of Acadia)

Labrador-tea (Rhododendron groenlandicum). (Photo by Charlotte Stetson/Wild Gardens of Acadia)

Black or Bog Spruce (Picea mariana) is a slow-growing conifer that favors wetlands and has short, dense, blue-green needles. Notably, the lower branches, when buried by the surrounding moist peat moss, can form roots; eventually these branches become individual trees. This often results in a circle of younger, smaller clones surrounding the mother tree.

The black spruces within the circle are clones and are genetically identical to the tallest spruce. (Photo by Helen Koch/Wild Gardens of Acadia)

Building a bog is challenging. When the Wild Gardens were developed in the early 60s, the initial location for the bog was not successful. In 1970, the park excavated a wet area beyond the brook for our current bog and added 20 cubic yards of peat from a bog in Penobscot owned by one of the Wild Gardens’ founders. In times of flooding, the Wild Gardens’ bog may not be accessible. When that is the case, we place typical bog plants in pots to show visitors.

Sources

Bogs and Fens: A guide to the peatland plants of the northeastern United States and adjacent Canada. 2016. Ronald B. Davis. University Press of New England. [This book includes a helpful list of northern peatlands that have boardwalks.]

A Focus on Peatlands and Peat Mosses. 1992. Howard Crum. University of Michigan Press.

The Plants of Acadia National Park. 2010. Glen H. Mittelhauser, Linda L. Gregory, Sally C. Rooney, and Jill E. Weber. University of Maine Press in association with the Garden Club of Mt. Desert, Friends of Acadia, and the Maine Natural History Observatory.

Rose pogonia (Pogonia ophioglossoides), a small, pink bog orchid. (Photo by Helen Koch/Wild Gardens of Acadia)

The Wild Gardens of Acadia offers park visitors an award-winning microcosm of Acadia’s uniquely varied plant communities.

Learn More