Doing science in a National Park is a dream come true for Schoodic Institute’s Chris Nadeau

August 2nd, 2023

August 2nd, 2023

(Photo courtesy Chris Nadeau)

Chris Nadeau has worked in natural resource management and science for nearly 25 years. He’s studied how best to monitor and manage rare wetland birds and owls, administered rabies vaccines to raccoons and skunks, and pet a dolphin. But climate change science captured his attention.

Last fall, Nadeau joined Schoodic Institute as the Climate Adaptation Scientist and says he’s thrilled to work so closely with the National Park Service to conduct science with a purpose.

A. Acadia National Park, like many places around the world, is changing. Climate change, invasive species, and increased park visitation are all producing new stresses on the unique natural resources in the park. Park staff are working diligently to incorporate these changes into their management, but there’s no playbook for dealing with rapid change. Luckily, we have an opportunity to apply creative solutions in such a way that we can learn as we go.

As the Climate Adaptation Scientist at Schoodic Institute, I work closely with park staff to apply cutting-edge conservation and restoration science that helps us learn to better manage park resources in a changing world. This involves staying up to date on recommended best practices in the field, but also using science-based approaches to evaluate which practices work best in Acadia.

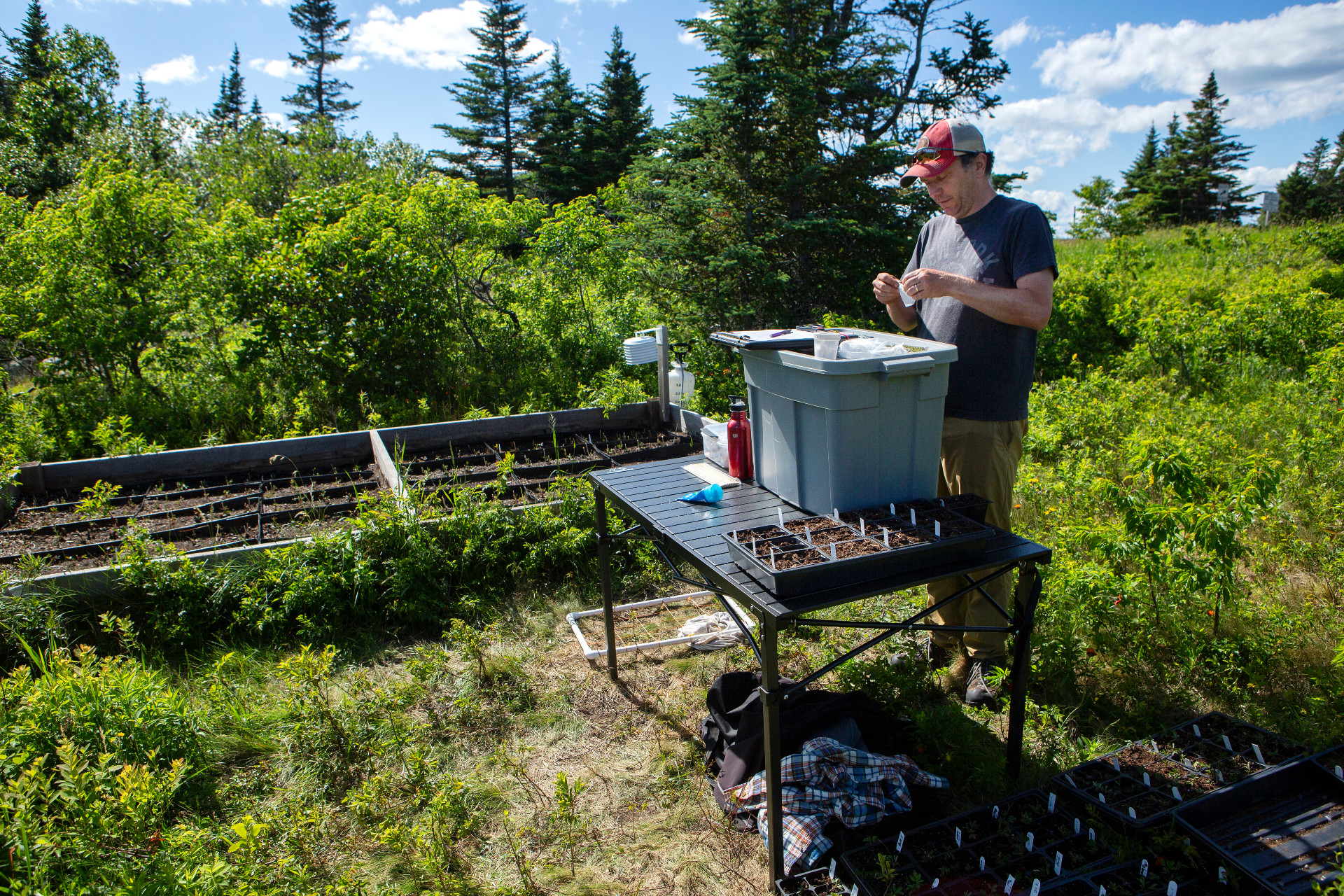

For example, I’m evaluating how best to preserve and restore vegetation on mountain summits, and how to ensure the restored vegetation persists during increasingly common dry summer heat waves. I am also testing multiple techniques to slow the spread of a persistent invasive shrub – glossy buckthorn – that has plagued two of the largest wetlands in the park: Great Meadow and Bass Harbor Marsh.

Nadeau takes measurements of a plant at the plot near the Blue Hill Overlook on Cadillac Mountain. (Photo by Ashley L. Conti/Friends of Acadia)

A. I’ve been working in natural resource management and science for nearly 25 years. Most of my work has involved working directly with natural resource managers to provide science-based solutions to natural resource challenges.

My career started by working many short-term positions, ranging from radio tracking mallard ducks in the Canadian Prairies to administering rabies vaccine to hundreds of wild raccoons and skunks. I then spent 10 years working as a Wildlife Biologist at the University of Arizona, where I studied how best to monitor and manage rare wetland birds and owls that live in underground burrows (aptly named burrowing owls).

After being exposed to academia in Arizona, I was hooked. I moved on to complete a master’s degree at Cornell University, where I developed a method to evaluate which species of greatest conservation need are most vulnerable to climate change and how we can reduce their vulnerability. I completed my PhD at the University of Connecticut, where I was introduced to Acadia and Schoodic Institute.

While completing my PhD, I received a Second Century Stewardship (SCS) Fellowship. My fellowship research showed how small, but cooler, locations in the park-for example, areas in the shade of a rock crevice-can conserve and accumulate biodiversity under climate change. Small, cool locations might therefore be critical for biodiversity conservation in the future.

I continued my work with the National Park Service and Schoodic Institute as a postdoc, where I started a longterm study evaluating whether collecting plants from warm locations and planting them in Acadia can make restorations on mountain summits more resilient to climate change. I continue this research now in my position at Schoodic Institute.

A. All too often, groups of experts disagree on the best practices for habitat restoration or natural resource management. The thing I like most about my job is turning those disagreements into something we can test.

For example, experts have suggested multiple methods for slowing the spread of invasive species. This summer, I’ll be working with park staff to compare some of those methods side-by-side to understand which one works best and why. I find resolving disagreements through science incredibly rewarding.

I also love spending so much of my time outside and mentoring early-career professionals. Most importantly, I enjoy working with an amazing team at Schoodic Institute, Friends of Acadia, and the National Park Service who are all doing inspiring work. To be honest, I can’t think of a part of my job I don’t love. Getting to do science in a National Park is a dream come true!

Members of the Acadia National Park Vegetation Crew and the Schoodic Institute put fencing around a plot to monitor the growth of glossy buckthorn. Chris Nadeau is pictured at center. (Photo by Sam Mallon/Friends of Acadia)

A. So much is changing in Acadia and beyond, from rapid declines in the abundance of birds to the shifting distributions of many species. Many of these changes require new research to understand how best to manage natural resources for the future. But we can only study so much at one time. Moreover, not all research will lead to improved management. Prioritizing the research that will have the biggest impact is the most challenging part of my job.

A. 2023 will very likely be one of the hottest years on record globally, and the Acadia region is warming especially fast. Warming and other climate changes are stressing park resources. Friends of the park can be especially helpful in documenting these changes. For example, they can use apps like iNaturalist and eBird to document how biodiversity is changing in the park on their next hike.

2023 will also be a big year as we ramp up research to understand how to restore ecosystems under rapid change. You will likely see our work in the Great Meadow, Bass Harbor Marsh, and on multiple mountain summits in the park (see “Research and Resiliency in Acadia”). There are lots of new signs at these sites explaining our work, but if you see us in the field, don’t hesitate to stop by and ask us what we are up to.

A. I was born in Canada, about an hour east of Toronto, Ontario, but I’ve lived in the United States for 20 years. My wife and I have been moving progressively north and east since we met in Yuma, Arizona at a bird-monitoring workshop.

I also love animals and have had the opportunity to interact with many interesting critters up close throughout my career. I’ve held hundreds of birds, pet a dolphin, played a game with a baby grey whale, and kissed a skunk.

Chris Nadeau checks the plot near the Blue Hill Overlook

on Cadillac Mountain. (Photo by Ashley L. Conti/Friends of Acadia)

A. Until this summer, I have only been to the Acadia region for intense research trips. I’ve rarely taken the opportunity to enjoy the area. My wife and I are so excited to be living in Ellsworth and learning about the region’s fascinating natural history. We already enjoy spending countless evenings trying to identify the many warblers calling in our yard.

This summer we hope to spend a lot of time hiking, biking, canoeing, and kayaking in the region. I’m also super excited to be starting new studies in the park.

As a scientist, starting new studies is a thrilling part of the job. The culmination of months of planning and the anticipation of learning is energizing.