BY SHANNON BRYAN

Acadia National Park is a “botanically fascinating place,” said Jill Weber, consulting botanist. “We have a suite of species that don’t get any farther south than right around our island, and we have a suite of species that from the south that don’t get any farther north than right around here.”

Mount Desert Island—including Acadia—is situated within the overlap of two range limits, making it a captivating place for the plant-curious to explore. The island’s terrain adds to the plant diversity: a variety of habitats fill a relatively small geographic space.

“Normally, to go from the ocean to a mountain top, you might have to go 100 miles or more,” Weber said. “But on our island, we’re going from the intertidal zone to the top of Cadillac in two or three miles. So, we have an incredible amount of diversity.”

Weber’s career as a consulting field botanist and plant ecologist in Maine spans decades and includes rare plant management in Acadia National Park.

Botanist Jill Weber. (Rhiannon Johnston/Friends of Acadia)

Plants are designated as rare when the total population of a species is limited to a few individuals or their presence is limited to a narrow geographic range. For some rare plants, both of these are true. Acadia’s forests and wetlands are home to at least 25 species listed as rare by the state of Maine.

Weber is keenly aware that new discoveries, even in a place you’ve known for years, could be just around the corner.

As the botanist and ecologist coordinator for the local Partners for Plants program, a volunteer project of the Garden Club of Mount Desert, she and a cadre of volunteers have spent the last 20- plus years surveying and monitoring rare plants in the park.

Working in tandem with park staff, they’ve gathered data on plants like seaside lungwort, Canada mountain ricegrass, mountain firmoss, Wiegand’s sedge, mountain sandwort, Nantucket shadbush, and boreal blueberry.

“Around that time, the park did not have a botanist,” said Weber, who helped launch the program with the late Sally Rooney. “Even with a botanist, they didn’t have time to monitor rare plants in the park.”

Jesse Wheeler, Acadia National Park vegetation program manager and biologist, concurs: “Without dedicated volunteers monitoring long-term datasets, like Partners for Plants, NPS managers may not know about species population shifts, and they wouldn’t be able to respond in a timely manner,” he said.

Early Partners for Plants efforts included invasive plant management and rare plant monitoring. Today, a half-dozen members of the Garden Club of Mount Desert continue to meet in the spring and fall to monitor designated plots of boreal blueberry.

Volunteers use one-meter-square sampling frames that are set up in the exact same spot every time, and they make note of

what plants are present within the frame in addition to boreal blueberry, as well as their abundance.

Volunteers with Partners for Plants survey Boreal Blueberry at the top of Cadillac Mountain. (Courtesy Jill Weber)

“Over time, we can see if blueberry is decreasing, but sheep laurel increasing—is sheep laurel pushing it out?” said Weber. “We can determine if a plant is present in the same area, or if it is popping up in new areas.”

While boreal blueberry is the most consistently monitored of Acadia’s rare plants over the last two decades, there was a time when Weber wasn’t sure it was a real thing.

“Years before I started doing this monitoring, I was on the botanical advisory group for the state of Maine, and we were talking about candidate species to put on the rare plant list,” she said. “Somebody suggested boreal blueberry, and I was like, that’s not a thing.”

At the time, she assumed the diminutive blueberry was simply a lowbush blueberry—merely petite because of its elevated location, as summit plants often grow smaller than their sea-level compatriots.

“And then molecular biology proved me wrong,” she said. “It is its own separate species.”

(In addition to boreal blueberry, Acadia is home to other species, including lowbush blueberry, highbush blueberry, and velvetleaf blueberry, whose leaves indeed feel velvety. These last three species can be seen together at the Wild Gardens of Acadia.)

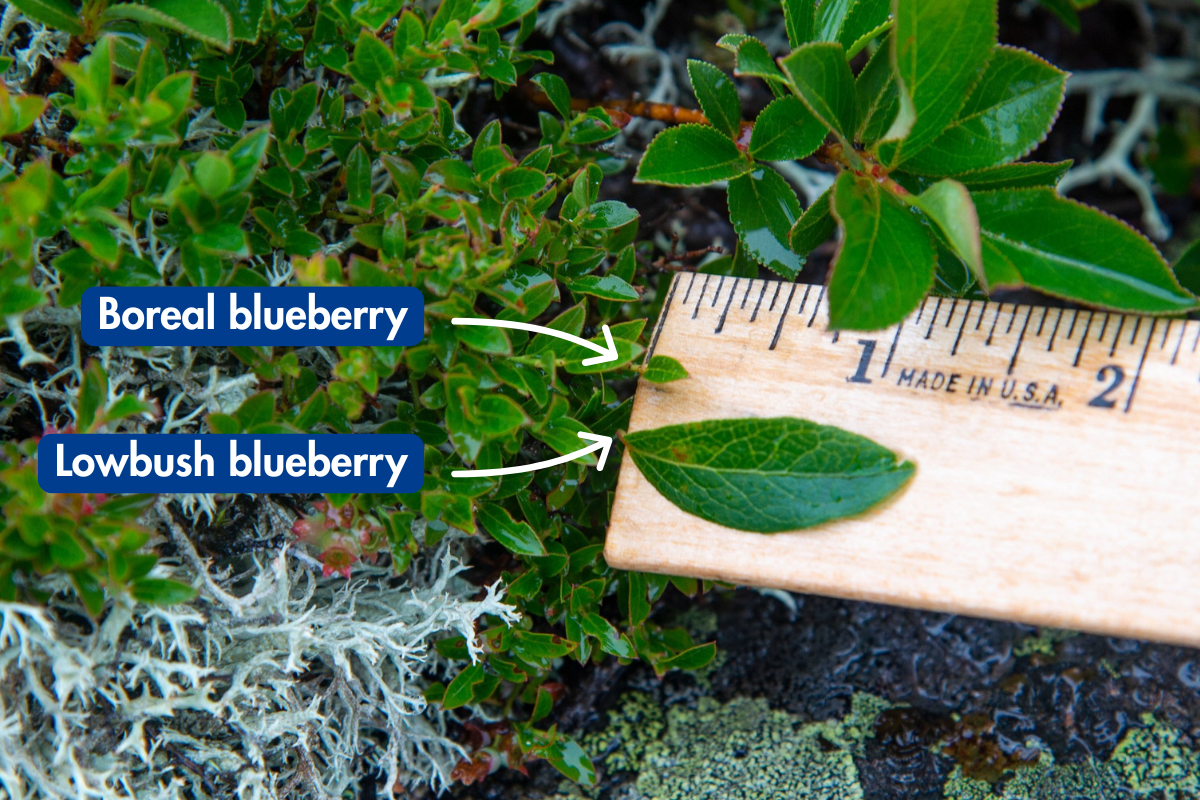

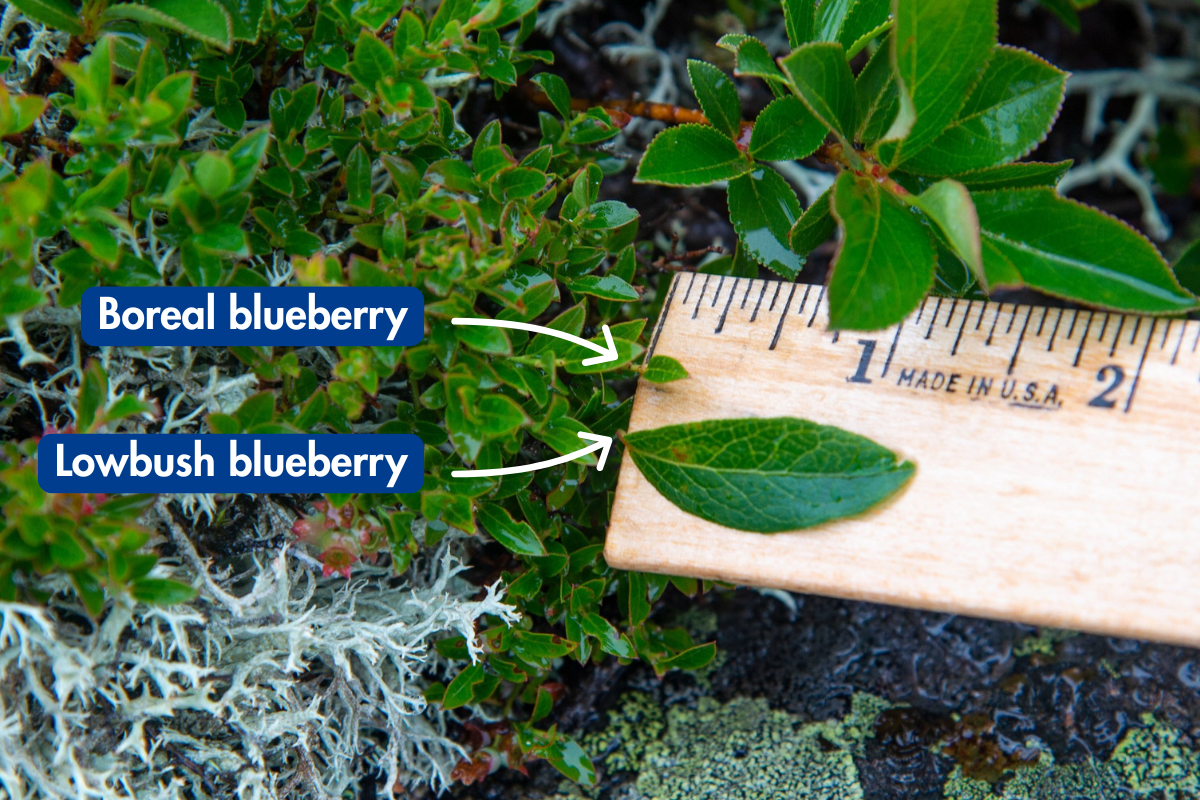

A boreal blueberry leaf and lowbush blueberry leaf are compared against a ruler, where it’s easy to see how much smaller the boreal blueberry leaf is. (Will Newton/Friends of Acadia)

Weber is a boreal blueberry fan. “The leaves are just so petite and lovely,” she said. “And it’s interesting that it looks so much like a lowbush blueberry, but it isn’t.”

Discoveries like that are a reminder that there’s still much to learn about Acadia’s plant species —hopefully before they’re gone.

“There’s diversity out there that you can’t detect with your eye,” Weber said. “How many other things are out here that we don’t know about yet?”

Even the boreal blueberry continues to pop up in unexpected places. The most recently identified plot was stumbled upon a few years ago by a group of consultants—Weber among them—who were on Cadillac’s summit to discuss restoration efforts with Acadia National Park staff. They walked out onto open rock near Cadillac’s West Lot, and there it was.

Compared to lowbush blueberry, with which park visitors may be quite familiar, boreal blueberry has shorter, more compact and branched growth and smaller flowers that appear 10-20 days earlier than lowbush flowers. They also have narrower leaves (although lowbush blueberry can also have slender leaves).

While boreal blueberry is often found growing alongside lowbush blueberry, neither one can be pollinated by the other since their bloom times don’t overlap.

“You can never have a hybrid between them,” Weber said. “The two stay distinct, which kind of makes me slap my thigh and go, ‘Well, I’ll be. That is kind of cool.”

A detailed view of a boreal blueberry plant beginning to fruit on the summit of Cadillac mountain. (Will Newton/Friends of Acadia)

Thanks to funding from the Garden Club of Mount Desert in 2024, analysis of two decades worth of monitoring data began

this past winter.

“Initial results show that boreal blueberry is relatively stable on Cadillac Mountain, where it is behind ropes and protected from trampling,” said Wheeler. “However, we need to continue monitoring to see if warming temperatures or other stressors lead to declining growth of this alpine plant.”

In partnership with the park and Schoodic Institute, Partners for Plants volunteers have also collected seeds from native plants, including juniper, goldenrod, flat-topped aster, green alder, and meadowsweet. Those seeds were passed to Acadia’s vegetation crew, who are using them in the experimental vegetation restoration plots on the Cadillac, Sargent, and Penobscot Mountains, where changing environmental conditions and foot traffic have damaged summit plants.

In the meantime, longtime volunteers continue to monitor. It’s an effort to which they’re dedicated, thanks to an affinity for plants, as well as the opportunity to see things that not every visitor gets to see, Weber said. And perhaps to spot something particularly rare and special.

“I like to say every plant has a story,” Weber said. “Whether it’s the pollination biology or when it leafs out, what its roots are attached to—every plant has something that makes you go, ‘How the heck? How is this even happening, and why has no one ever told me this?’”

“It makes you want to go back for more.”

SHANNON BRYAN is Friends of Acadia’s Content and Website Manager.

Join

Join Donate

Donate Acadia National Park

Acadia National Park