Making Way for the Night Sky

Lighting assessments and replacements in Acadia aim to welcome the dark night sky, helping birds, bats, fireflies – and humans, too.

August 10th, 2025

Lighting assessments and replacements in Acadia aim to welcome the dark night sky, helping birds, bats, fireflies – and humans, too.

August 10th, 2025

BY TREVOR GRANDIN

Acadia at night is an ecological wonder.

As twilight falls, the darkest parts of Acadia’s forests become hubs for one of nature’s most iconic bioluminescent critters—lightning bugs. These dark-dependent insects hover drowsily amongst the trees in search of mates, and photographer John Putnam is there to document their dazzling displays.

For hours at a time, Putnam and his camera lie in wait, often braving the park’s less charismatic mosquitoes for his craft. He takes hundreds of exposures over a single session, stitching them together to create light-filled portraits that showcase these ephemeral insects. Putnam said that equal parts anticipation, childlike wonder, and appreciation for Acadia keep his firefly interest alive.

“I really wanted to take this one love that I had of fireflies and combine that with this other love of Acadia,” Putnam said. “I almost don’t feel the mosquito bites when I’m out there doing that, because I have the privilege of being able to see both of those things together.”

But the twinkling subjects in Putnam’s forest portraits could be in danger. Expert opinion and anecdotal evidence suggest populations are declining in many lightning bug species worldwide. Maine boasts 15 species of fireflies—including a winter firefly—according to Firefly Atlas, a collaborative project focused on understanding and conserving the diversity of fireflies in North America.

Although the reasons for these declines vary, light pollution is a threat that persists in both urban and rural environments.

Unprotected artificial lights can outshine their glow-in-the-dark communications, and fireflies only flash half as often as they do in natural environments, hampering their ability to mate and reproduce.

A composite image shows the trails of fireflies flickering along the edge of Jordan Pond. (Avery Howe/Friends of Acadia)

But the threat of artificial lights doesn’t affect one animal at a time; it pervades entire ecosystems. Insects that are attracted to Acadia’s artificial lights are easy pickings for the park’s bats, and though these abundant food sources are a boon for nocturnal animals, this buffet has cascading effects. When outdoor lights cause moths and other nighttime pollinators to coalesce in one location, bats and nocturnal birds change their behavior to take advantage of this newly abundant food source. Long-term shifts could change insect populations, pollination rates, and animal interactions, leading to weak plant communities and unsteady food chains. That’s where national parks come in.

In 2006, for the first time, the National Park Service explicitly extended its mission to night skies, stating that it will protect the “natural lightscapes of parks” and minimize artificial lighting impacts throughout the National Park System. For Acadia, this means replacing the lights in park campgrounds, mapping light locations, measuring light pollution, and interpretive programs focused on night sky appreciation.

Strong partnerships are the backbone of Acadia’s night-sky research. In the 2000s, the park worked with the gateway communities of Bar Harbor, Tremont, and Mount Desert to adopt new outdoor lighting standards into their land-use ordinances. The following year, the park partnered with Friends of Acadia, the Bar Harbor Chamber of Commerce, and others to launch the Acadia Night Sky Festival, which ran from 2009 to 2019. Today, park visitors can attend ranger-led Night Sky programs throughout the season.

Also in 2009, the park received a National Park Foundation grant to inventory and assess all outdoor lighting in Acadia. That assessment led to the replacement of more than 40 non-compliant lights at Blackwoods Campground, made possible by generous donations. Outdoor-lighting company Musco Lighting provided “fully shielded light fixtures,” which direct light downward and greatly reduce light pollution. The Yawkey Foundation, through Friends of Acadia, funded their installation.

Since 2013, Worcester Polytechnic Institute’s (WPI) “Dark Sky” project has engaged student researchers in a continuous, collaborative project to stem light pollution within the park.

Students from Penn State conduct surveys at the summit of Cadillac Mountain to capture visitor responses to the changing lights. (Courtesy photo)

Standing atop Cadillac Mountain or within Acadia’s forests, WPI students peer at the sky and take measurements using Sky Quality Meters. Through these readings and light inventories, researchers gauge the clarity and overall darkness of the night sky while identifying light fixtures that cause the most harm.

Professor Frederick Bianchi, director of WPI’s Bar Harbor Project Center, said that after years of data collection, the next phase of the project is creating a discreet action plan for the park.

“I think it’s an important and good problem to work on always, because it is solvable,” Bianchi said. “Solvable [to] the extent that we can make the lights compliant. We can. Technology is changing. We can take care of Acadia.”

While the bulk of Acadia is dark at night, one lit structure in the park—such as the Cadillac Summit Road entrance station—has a disproportionate impact than if it were in a fully lit environment, like downtown Bar Harbor.

“One reason I like this project is that the fix is so easy,” said Bik Wheeler, lead wildlife biologist at Acadia National Park. “It’s either turning off lights or switching them out.”

A collaboration between Boise State University, Penn State University, and the Natural Sounds and Night Skies Division of the National Park Service is testing solutions that could make nights safer for animals and people alike. Funded by the National Park Foundation, the research project seeks to balance the needs of wildlife conservation with enhancing visitor experiences in national parks, including Acadia, Great Smoky Mountains, and Grand Teton.

In Acadia’s forests, researchers installed bat detectors with different colored lights—white, amber, yellow, and red—to better understand how the mammals react to different hues. Red light is considered best for wildlife, and humans can actually see better using red light as well. (Visitors to Grand Teton now have the opportunity to view the Milky Way since the park switched to red-hued lighting.)

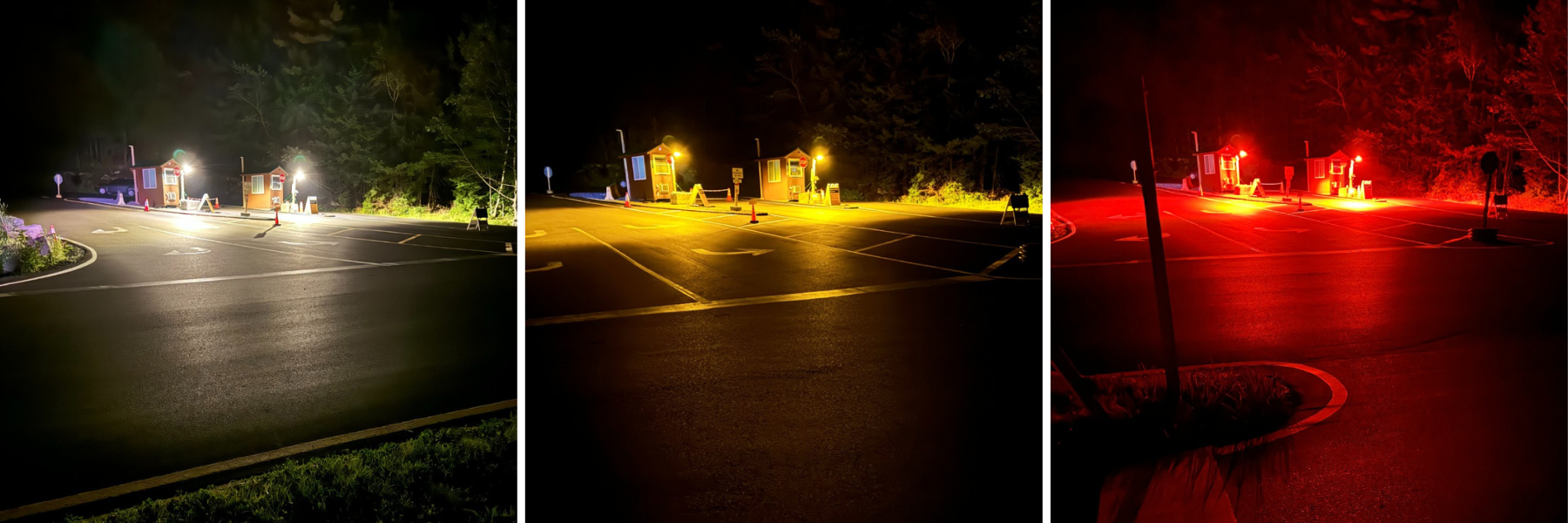

Researchers in Acadia installed these variously colored lights at Blackwoods Campground and on Cadillac Mountain and then interviewed visitors about their experiences and thoughts about the new fixtures.

Lights of different hues are tested at the Cadillac Summit Road entrance station during a lighting study that assessed the effect of different lights on wildlife and visitors’ experiences. (Adam Gibson/NPS)

Surveyed visitors were largely in strong support of adjustments to lighting in the park, from changes in the hue and brightness of the light fixtures to reducing the number of lights overall. When they found out the benefits to wildlife, their support increased.

These collaborations aren’t just informing Acadia’s management; they have the chance to impact decisions in parks across the country.

“If we can find a lighting system that fits all of those different ecological areas and combines social and biological science, then we can change lighting standards service-wide,” said Adam Gibson, social scientist at Acadia National Park. “And that’s the kind of thing that really excites me, not just about what we’re doing in Acadia but potential changes to national parks everywhere.”

Some people can trace their appreciation for nature back to a single spark from childhood—climbing trees in local parks, searching for starfish in shallow tide pools, or catching fireflies on still summer evenings. Soon those sparks of appreciation

grow into roaring fires that last into adulthood. Initiatives like dark sky protection give credence to the park service’s mission to leave parks unimpaired for future generations, allowing that spark to catch while looking skyward in wonder or simply marveling at glowing fireflies.

TREVOR GRANDIN is a freelance writer and former Cathy and Jim Gero Acadia Early-Career fellow at Schoodic Institute.