Managing Climate Change in Acadia is Tougher Than it Sounds

November 24th, 2021

Managing Climate Change in Acadia is Tougher Than it Sounds

November 24th, 2021

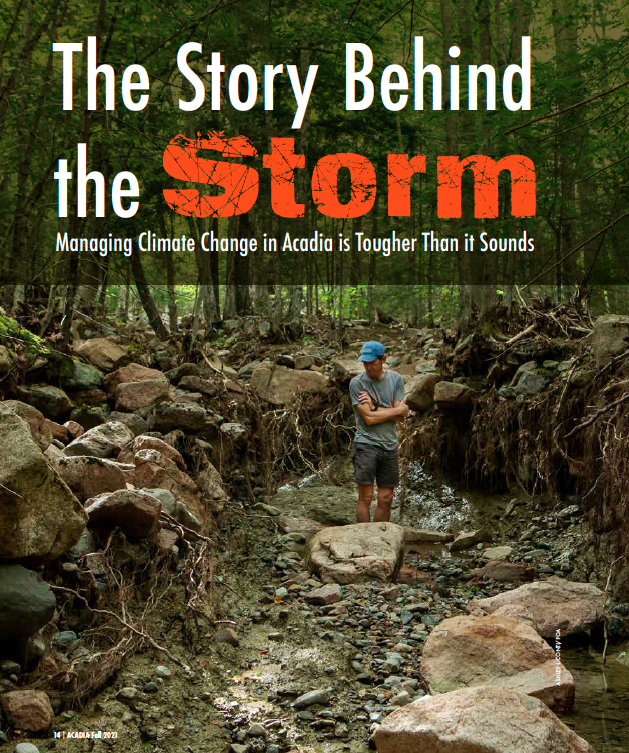

Cover image for Acadia Magazine story. Brian Henkel examines the damage to Chasm Brook near the Seven Bridges section of carriage road.

BY REBECCA COLE-WILL

On a rainy Friday morning in early July, I joined Brian Henkel, Wild Acadia Coordinator for Friends of Acadia, Gail Gladstone, Acadia’s Cultural Resource Manager and Bik Wheeler, Wildlife Biologist, as we cautiously drove a van behind the locked gate on the Eagle Lake Carriage Road. Our destination was the segment of carriage road that had been washed out in an unprecedented storm on June 9th. Our goal was to better understand the impact of the storm that led to the closure of approximately 10 miles of carriage road and how that damage further impacted the forests and streams below.

The storm had unleased torrents of rain down the steep slopes of the Around the Mountain segment of Sargent Mountain. The raging water tore through carriage roads, overwhelmed ditches, and filled drains beyond capacity. Water flowing over the carriage roads eroded deep gouges and exposed the core materials of the carriage road base that hadn’t seen the light of day in almost a century.

The park’s facilities team responded quickly to assess the damage, estimate the cost of repairs, and obtain emergency funds for repairs. By the time we walked the road, from the Seven Sisters Bridges area up and around the mountain, some lower sections had already been repaired so skillfully that you might not even realize they had been damaged.

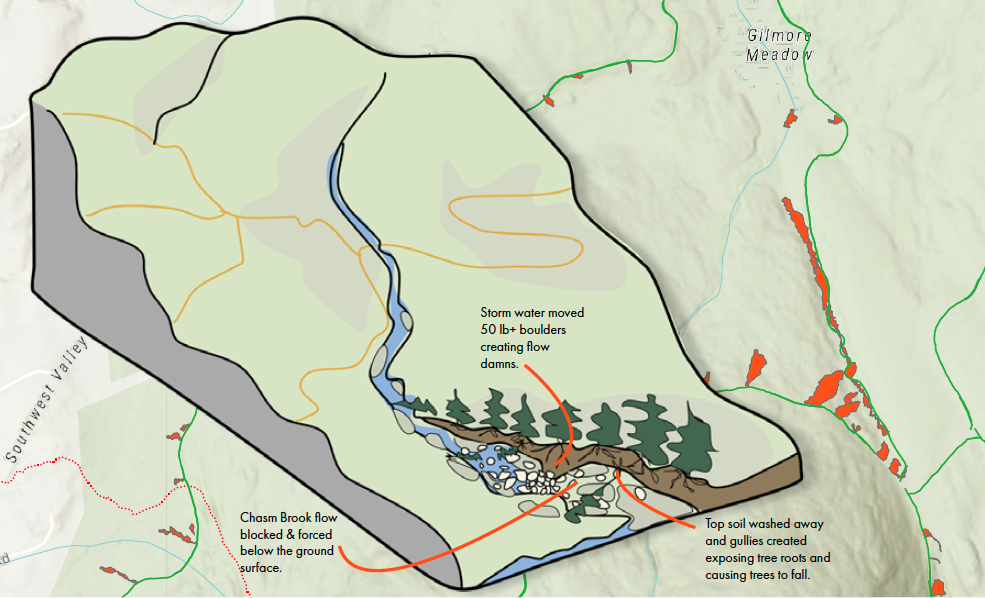

But we were seeing other damage. All that carriage road mix of gravel, sand, and cobbles, along with roadside vegetation and soil was spread out into the forests, streams, and wetlands through which the carriage roads wend.

As we walked the roads and roamed into the surrounding forest, we were saddened and overwhelmed by the damage to the natural resources. “Deltas” of gravel covered expansive areas adjacent to streams, sealing off the ground vegetation. Open areas next to the roads where blueberries had thrived were now covered in gravel. Further down slope, the bedrock was scraped clean of vegetation and soils, soils which had developed over millennia. Cobble “end moraines” marked where the water torrents had finally dropped their load.

We saw where Chasm Brook had taken the brunt of the storm. Its banks were scoured and undercut, leaving tree roots exposed. In areas adjacent to the streams, red spruce roots were exposed where virtually all the protective duff layer had been stripped away by the flow of water loaded with gravel. When forest ecologist Kate Miller saw the damage, she lamented, “Those trees are probably going to die.”

So, as we walked and mourned for the devastation, we also talked. What should we do? What could we do? Could the gravel burying the natural forest floor be safely removed? Should it remain in place in hopes that the landscape could heal itself? Can the soil layers be repaired to possibly save some of the trees? How will this affect the health of the downstream wetlands?

Illustration of effects of the storm waters which cut valleys in the loam layers, skimmed off and deposited massive amounts of carriage road gravel into the forests, moved rocks and boulders and exposed vulnerable tree roots along the way.

We met as an interdisciplinary team of resource managers to begin to figure this out. Karen Anderson, the park’s geographical information specialist (GIS), built a mapping tool linked to a database of impacts. The resource teams pivoted from their normal seasonal work to begin an intensive and expansive field-mapping exercise, including staff and technicians from air and water, invasive plant management and wildlife programs, augmented by the Northeast Temperate Network forest inventory team, Schoodic Institute technicians, and Friends of Acadia staff.

The teams mapped the extent of impacts, almost 125,000 m2 (roughly 10 acres) of deposition and eroded carriage road materials displaced into the environment. They identified the high priority resource areas near critical habitat that will need protection and consulted with technical experts in the National Park Service about future management needs.

Acadia’s Physical Science Technician Erica Doody measures the depth of scour that occurred to a section of Chasm Brook.

The most sensitive resource areas are streams and wetlands. Bik Wheeler is concerned about the impact of altered water chemistry on herptiles, especially salamanders that are already under threat. Jesse Wheeler, botanist, recommends close monitoring of wetlands, some of the park’s most sensitive resources. With sediments deposited into these areas, the threat of disturbance-loving invasive plants like cattails and purple loosestrife is increased.

In the short term, we will minimize impact to streams and wetlands by strategically installing some erosion fencing, to “stop the bleeding” as biologist Bill Gawley put it. We will apply for restoration funding to support the effort of our resource teams, and we will continue long-term monitoring to understand how the forests, streams, and wetlands respond.

This is a climate-change story and how we respond and tell this story is central to our work now. We will use the understanding of what happened to build adaptive approaches for the future. This type of storm was unprecedented in the history of Acadia, but that is no longer the case. We have recognized, within our work with Wild Acadia that we are experiencing rapid environmental change. We can no longer look to the past as a guide for how to manage our natural resources. (See related story: Acadia’s Changing Climate, pages 14-17, Acadia magazine, Summer 2021).

As we work to repair the damage both to the carriage roads and the natural environment, we’ll need to look for solutions that best prepare Acadia for the changes we’ve already seen and those we expect in the coming decades.

This story most certainly is to be continued.

Water rushes down Railroad Brook near Cadillac Mountain in Acadia National Park during the June 9 storm. (Photo from video by Dan Meggison)

Acadia National Park Resource Management staff prepare to collect field data for use in assessing the damage to the streams and forests from the storm.

Deposits of carriage road gravel fill the brook below the Seven Bridges area.

Acadia’s Vegetation Biologist Jesse Wheeler measures the depth of scour to the stream bank.

REBECCA COLE-WILL is the Chief of Resource Management for Acadia National Park.

This story appeared in the Fall 2021 Acadia magazine.

Congressional Leaders Visit Acadia as part of Climate Change Tour